Maurice Brosnan: Club finals show every day is still a learning day under Gaelic football's new rules

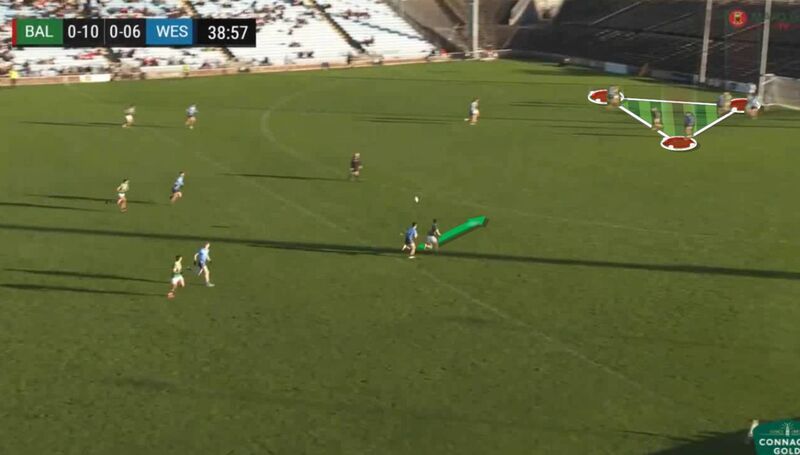

Appetite and hunger are important components on breaking ball. So is structure. Pic: ©INPHO/Dan Clohessy

Every game has its patterns and every season its heresies. When the crowd turns, few bother to argue back. As the talk turned to the death of Jim McGuinness’s zonal defence after Donegal’s heavy All-Ireland final defeat, Enda McGinley was one of the rare voices going against the grain.

Kerry had picked their way through the system with ruthless precision, but the three-time All-Ireland winner wasn’t ready to write the obituary.

"Against the vast majority of club teams and county teams for that matter, the zonal defence as Donegal and Armagh have shown is highly effective and will win you 80-90% of games,” the RTÉ pundit said.

“Does it have its problems? Yes. And so does the man-to-man. There is no easy solution.” One particular set play is now exposing the limitations of a man-to-man system. It’s being rolled out repeatedly and with striking success. This is an evolution of what Rory Gallagher once weaponised with Derry and what Armagh evolved after.

The tactic of flooding the square with bodies and isolating a pacey forward in space has become commonplace. Across several county finals last weekend, teams turned to it instinctively.

There are obvious benefits to this set play. All it takes is for one defender to be beaten and the attack has enormous space to exploit. If a coach has a player like Gavin White, Eoin Murchan or Tom O’Sullivan at their disposal, why wouldn’t they manufacture as many openings as possible to let them loose against a single opponent?

These are the questions occupying coaches ahead of the 2026 inter-county season. Further defensive innovation feels inevitable. The problem with the example above is that if a team doesn’t track every attacker who drifts close to goal, the opposition will expose it. Once teams sense the defence isn’t going man-to-man, they’ll drop ball in on top of them.

Is this where the next wave of goalkeeper innovation emerges? Will we see a refined hybrid, with pressure high up the field and defenders folding centrally closer to goal?

McGinley also made the point that the defensive system is a secondary concern; possession is the primary one. Establish a foothold in midfield, secure a steady supply of ball, and limit the opposition’s chances. A crucial element of last July’s decider was that Kerry had significantly more team phases than Donegal.

When it came to net points per kick-out, Donegal and Kerry were two of the top three teams in the country in the Sam Maguire series, post-provincial championship, with Dublin third.

For understandable reasons, that level of sophistication has yet to manifest in club football. At the elite level, goalkeepers can clip a restart short around the arc and powerful defenders can break a press to carry their side upfield. Lower down the ladder, that same luxury doesn’t always exist.

Westport had chances to win just their second ever Mayo SFC title on Sunday, but had to settle for a draw after a late two-point free from Ballina’s Frank Irwin. Repeatedly, Ballina only pressed three players to cover Westport’s four defenders on the arc. Despite that, they only went short with two kickouts. In the end Westport scored 0-5 from their kickout and conceded 1-1. They lost almost half of their long kickouts and were cleaned on breaking ball, winning just 29%.

That is the numbers game that is a crucial factor with the new 40-metre arc. Appetite and hunger are important components on breaking ball. So is structure. Ballina were able to consistently outnumber Westport in the middle because they didn’t have to fully commit to the press.

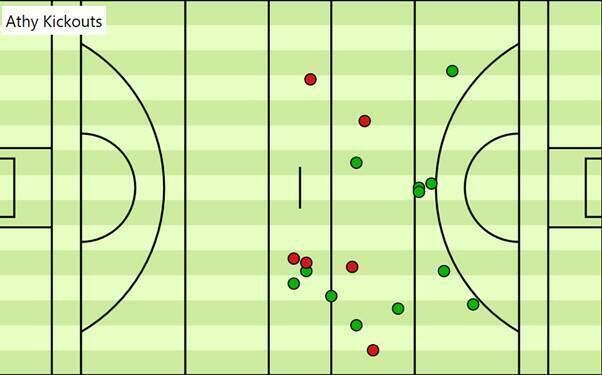

This was a significant part of Athy’s ability to end Naas’ bid for a fifth successive Kildare title in Cedral St Conleth's Park. Naas conceded kickouts until the final quarter and paid dearly for it.

In the end, Naas retained just 50% of their own kickouts while Athy finished at 67%. The eventual winners had more phases, shots and a higher possession-to-shot in the tie. Had they been a bit more clinical, it would have been a convincing victory.

The theory behind conceding kickouts previously was that defences backed themselves to turn the attack over more than they would get shots off. It was clear after six minutes this wasn’t going to be the case, Athy had two scoring opportunities from their first two kickouts. In total, they won 12 kickouts and had ten shots. Even if it ended in a wide, they were pressing Luke Mullins’ kickouts at the other end, effectively ensuring they would enjoy far more possession.

Alex Beirne had a late two-point free that could have levelled the game, but manager Philly McMahon seemed to urge him to work it short. Eventually they went for the one-point attempt and it drifted wide.

Managing that endgame is another work-on. In the Kerry SFC semi-final, Dingle just about held on through a thrilling finish. They led 1-16 to 0-16 as the hooter sounded, but Tom O’Sullivan went for the score and hit the post. A red wave began its pitch invasion behind the goal and had to be beckoned back.

A ball dropped into the square was plucked by AFL ace Mark O’Connor, who blasted it out behind his goal instead of over the sideline. Cue another premature invasion.

The Geelong star was superb throughout, yet like many others he’s still adjusting to the new order. Right now, every day is a learning day.