Colin Sheridan: I couldn’t hate him. I just wished Diarmuid Connolly was ours

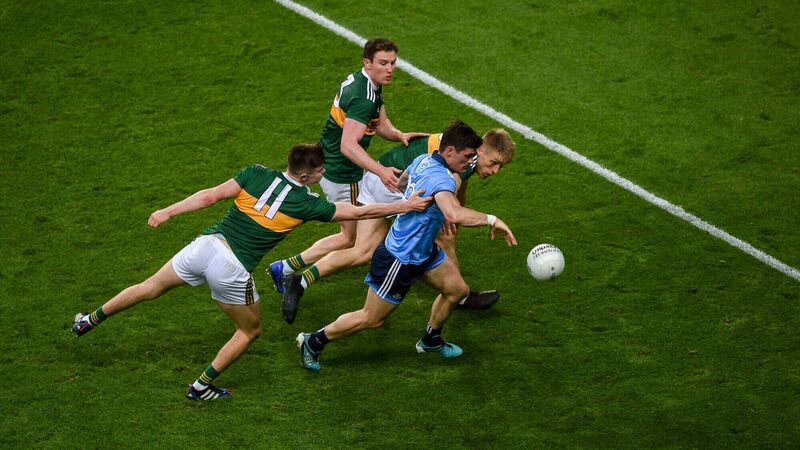

Diarmuid Connolly of Dublin in action against Kerry players, left to right, Seán O'Shea, Tadhg Morley, and Killian Spillane during last year's All-Ireland final. Picture: Daire Brennan/Sportsfile

In case you hadn’t heard, Diarmuid Connolly retired from inter-county football last week. There was no cameo on the Late Late with Ryan, and no tell-all expose in the Sunday magazines.

A simple statement released via the Dublin GAA website told us all he wanted us to know, and so the most flamboyantly gifted footballer of the last decade exited stage left without giving us a chance to say goodbye.

It’s unlikely he spent the weekend refreshing his screen to gauge reaction, count likes, retweet retweets. Maybe the old romantic in me, but, in my mind I frame his departure as if the closing scene of Good Will Hunting; Connolly’s Dublin team-mates pulling up to his house to pick him up, only to realise he is not there. A two-line note left for Dessie Farrell, explaining that he had to go see about something or other. And finally, a tracking shot of his car, within which he sat, bedecked in a sleeveless tank top, driving west, all scored by Elliot Smith’s Miss Misery.

Like Will Hunting, Connolly was undeniably a genius, but his genius was not secretive. Connolly solved the most difficult theorems on the grandest stage, time and time again, under the greatest pressure. He is perhaps the first contemporary gaelic footballer to give us the ‘highlight reel’ —montages of audacious plays executed effortlessly. We will never know how easy it was for him, but he sure made it look so.

Academics will teach us genius falls broadly into two categories; the conceptualists (Picasso) — those who just see it and do it, and the experimentalists (Paul Cezanne) — those who toil for years and years, trialling, failing and refining.

Connolly was Gaelic football’s great conceptualist; he saw, and then he did. It didn’t always come off, but when it did, it usually left us breathless, regardless of our bias.

That Connolly achieved what he did under Pat Gilroy and Jim Gavin is also telling. Neither men suffered fools, or overly-indulged talent, especially at the potential expense of the collective. Given our proclivity for cultivation of the myth of the mysterious, characters such as Connolly often morph into difficult, divisive totems.

In the absence of communication, perception and reality are often the same. The Dublin camp of the last decade was a study in both the Sicilian discipline of omerta, and — on those rare occasions there was noise — misdirection. While that dynamic undoubtedly served the group well, it left the rest of us to speculate. Any prolonged absence from Connolly was treated with the gravest suspicion.

Though most of us knew nothing of the real him, we applied the formulaic ‘tortured genius’ overlay and came up with the usual suspects of narratives; (a) off the rails, (b) spat with manager, (c) gone hurling, (d) Boston, (e) off recording a grime record with Aslan. There were times he did not help himself, but then, help himself to do what exactly? Conform to our ideal of what we expected him to be? The truth may only emerge as the multiple winners retire and write their well-deserved books, but so far the evidence points at Connolly being nothing but a positive influence while he was there.

One narrative which floated like a plastic bag on the wind last spring was Gavin wanted to win an All-Ireland without him, as if proving his system, his process did not need nor want an outlier like Connolly. Well, one piece of whimsical conjecture deserves another; how about Gavin instead choosing to include Connolly (after his aborted trip to the US) in Dublin’s five-in-row bid, not solely for the benefit of the team, but for the benefit of Connolly himself? If there is in fact a morsel of truth in this, it points at Gavin being a far better man manager (and person) then his steely reputation often portrayed.

He gambled on Connolly last season — twice — at crucial moments; once in the drawn final when it flagrantly didn’t work, and once in the replay, when it blatantly did.

Gavin would never have done this as an act of charity, but as a leap of faith in someone he clearly trusted, not to uphold his lauded process, but to be himself; a footballing alchemist.

Connolly obliged. His cameo in last year’s replay epitomised his entire Dublin career. There was the ridiculously careless — an unforced turnover after gliding upfield 40 metres. There was an incomplete fancy flick, when the simple thing — the Jim Gavin Dublin thing — to do was to secure possession and walk the ball back 30 yards.

He mixed this pair of faux pas with the utterly sublime; dispossessing his opponent with an unmerciful hit, followed by a pass worthy of a collection of poems.

The cynics will say this and that — but the hard truth is, there was no other player on the field who would have had the balls to try that pass in any context, never mind Dublin — the most risk-averse team in history — being a single point up in an All-Ireland final replay, and simply no other player anywhere who could have executed it. He did both.Dublin scored.

Connolly was of course polarising. There was darkness; a beast that lurked beneath the beauty. Sometimes he was both at once. Now that he is gone, I know what my abiding memory of him will be; in 2017 he warmed up in front of where I sat in the lower Hogan. The game was suffocating in its intensity. We didn’t fully understand who Dublin were then. Mayo had them.

Connolly waited like an assassin for Gavin to give him the nod. It only took him till half-time. As the clock ticked south, and the air got thinner and thinner, Connolly did more and more. He carried and hit and blocked, and, in the penultimate Dublinattack, attempted a shot from fifty yards, likely sick of the one hundred phases of keep-ball that preceded it. The shot drifted wide, and Connolly was visibly annoyed.

From the ensuing kick-out, he took the ball from the 65’ and ran directly at Mayo, winning the free Dean Rock would ultimately point to win Dublin their All-Ireland.

At that moment, my heart broken, I couldn’t hate him. I just wished he was ours.