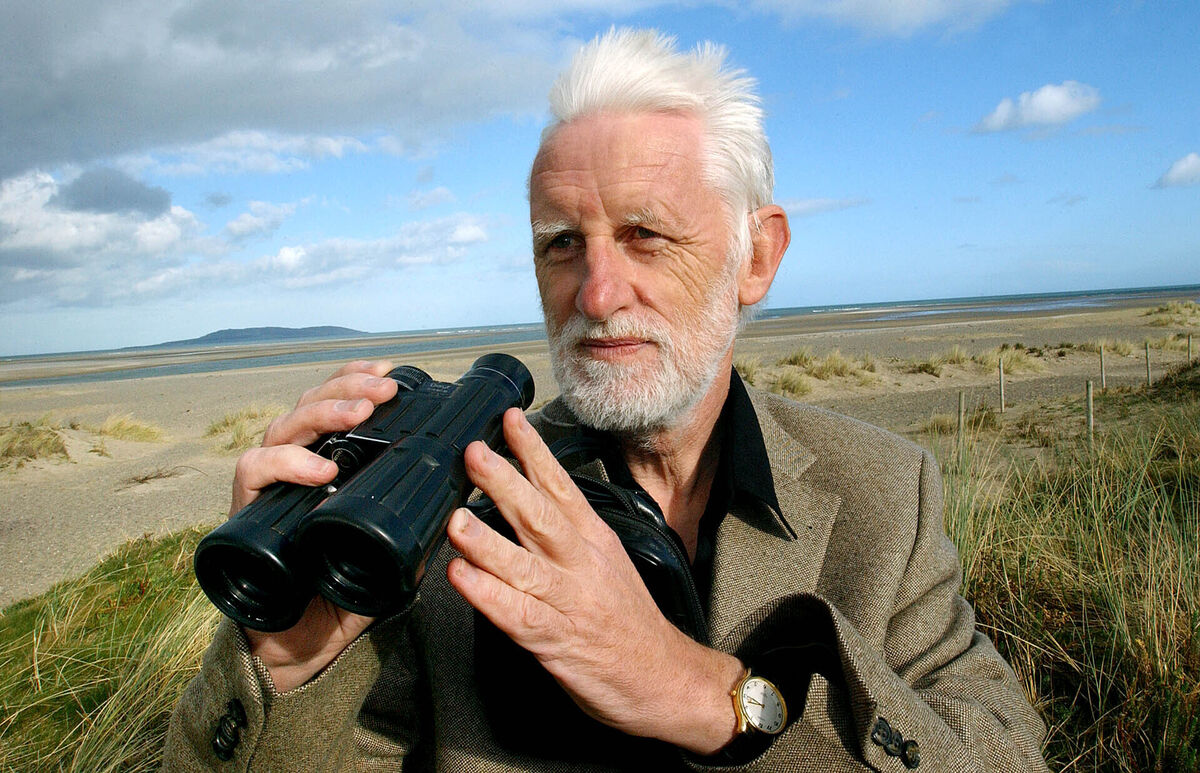

Richard Collins: Why civilisation has a downside for humans and animals alike

House wren feeds bug to baby birds in backyard birdhouse

Our hunter-gather ancestors seem to have been taller and healthier than the farmers who succeeded them. This led geographer Jared Diamond to claim that adopting a settled way of life was ’the worst mistake in human history’. Becoming ‘civilised’ had a downside.

Humans were not alone in radically changing their way of life. Songbirds undertook a similar revolution. Many so-called ‘garden’ birds used to live along the fringes of woods. Seduced by the new habitats we created, and the relentless destruction of the forests, they became ‘the new kids on our block’.

The change was largely successful but, as with humans, there was a price to be paid. Even today, songbird pairs nesting in suburban gardens produce lighter youngsters than their rural counterparts. Why early farmers and songbird chicks became smaller has intrigued scientists.

Archaeologists believe that ancient hunter-gathers enjoyed a much wider range of foods than the settled people who followed them. Early farmers, however, subsisted mainly on the species they could grow and the goats they kept. A restricted diet contained less protein and lacked nutrients important for growth. And there were other threats. Teeth, for example, began to rot. Staking out and fencing off land, raised hackles. As Rousseau claimed, the birth of private property spawned conflict violence and premature death. ‘How can you buy or sell the sky, the land. The idea is strange to us’, asked Chief Seattle when President Franklin Pierce sought to purchase tribal lands in 1855.

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst set up 38 nest-boxes for house wrens, a close relative of our Irish ‘king of the birds’, in suburban gardens. Recorded calls of owls and falcons were then played over strategically located speakers. Wren nestlings were weighed every three days.

Previous studies had shown that chicks raised in back-gardens weighed 10% less than those raised in rural areas. The young wrens weighed in this experiment were a further 10% down on average. The extra reduction in weight, the researchers believe, was due to the owl and falcon calls played to their parents.

Birds near human habitation run the gauntlet of many enemies, chief among them being the domestic cat. Predators are more numerous in suburbia than they are in wilder places. It is difficult for songbirds to conceal nests in manicured gardens and protect their emerging chicks. Parent birds, constantly watching their backs, have less time to find food for their young, so nestling weights are lower.

Garden birds live in a state of constant vigilance. Zoologists, the researchers think, have focused on what inspires fear, but tend to overlook the fear factor itself and its possible impact on wildlife behaviour. Fear can be disabling, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt knew. ‘We have nothing to fear but fear itself’ he declared in his 1933 inaugural address!

These findings help explain the mysterious ‘predation paradox’. Counterintuitively, as the number of predators increases in wildlife populations, the per capita rates of attack on prey fall. This research results suggest that fear, distracting adult birds from their parental tasks, is responsible for the reduced weight of their chicks.

- Aaron Grade et al. Perilous choices: landscapes of fear for adult birds reduce nestling condition across an urban gradient. Ecosphere. 2021.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates