Terry Prone: We were told vote spoiling was pointless — but it sent a message

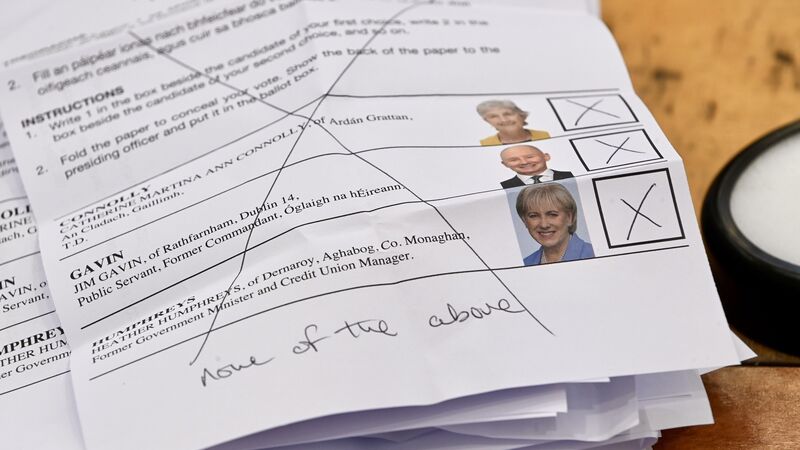

None of the above: Around 190,000 people spoiled their ballot. Picture: Larry Cummins

Within half an hour of the opening of the first ballot boxes, the triumph and tragedy of this presidential contest were clear.

The triumph belonged to Catherine Connolly. It was so indisputable that she was able to announce her intention to head to Dublin before most people had woken up or tuned in.

The triumph also belongs to the parties of the left, which for the first time co-operated to run a campaign that was modern, sophisticated, confident, and effective. As a result, we not only have a president, but (to quote Dana) we have an electoral precedent, too. Broad spectrum triumph, then.

The tragedy is that this has been the half turnout and spoiled vote election.

It would seem that only four people out of 10 actually voted. That is not to diminish the Connolly victory. It is nonetheless a small democratic tragedy that so many people couldn’t be bothered to vote and saw no benefit to themselves in exercising the franchise.

That’s not counting what looks like a quarter of a million people who overtly spoiled their votes or voted for Jim Gavin which, in the final analysis, amounts to the same failure to meaningfully participate.

Now, the interesting thing is that, in the days before polling, every establishment worthy, including the Election Commission, lectured the electorate about how pointless it was to spoil your vote. The voters didn’t buy it. They seriously didn’t buy it.

An amazing number of voters in constituencies right around the country spoiled their votes and, in the process, proved the authorities wrong.

If you listened to or read early coverage on Saturday morning, you encountered reportage of precisely what people said in their vote spoilage. This wasn’t just rejection of candidates. This was people bringing their own Sharpies in sufficient numbers to leave messages which — as it turned out — made it efficiently into mainstream media. This was vote spoilers out-polling Jim Gavin and Heather Humphreys combined in some constituencies. This was — but in only one case of which we know — excrement was used to spoil a vote.

The implications of the spoiled vote story are many. First of all, everybody who said vote spoiling was pointless was proven wrong and may even have stimulated the unprecedented vote spoilage, as some people who resented being lectured may have set out to prove the lecturers wrong.

Secondly, spoiling your vote, for the very first time in Irish electoral history, proved to be a highly functional method of sending messages. The messages were wildly different to each other, but that’s beside the point.

From every constituency, they were faithfully listed off by one TV/radio/online reporter after another. Everything from Maria Steen’s handbag to Enoch Burke, with anti-immigration sentiment thrown in and various points about government performance.

The larger political parties may try to draw comfort from the lack of homogeneity among the vote spoilers. They will do so at their peril, because the very variety of the vote spoiler motivation speaks to voter dissent and dissatisfaction as well as civic illiteracy.

One issue worth exploration is the degree to which an online campaign motivated vote spoilers and the degree to which the action was spontaneous.

The proportions — a fifth in one box — argue that the online campaign may have been what made the difference between spoilage in the past and, this time, moving it from a couple of percentage points to 20% in some cases. The figures are not final, but the estimates suggest around 190,000 votes were spoiled. And that 100,000 votes were cast for Gavin; effectively more spoiled votes.

The landslide nature of Connolly’s victory meant that, by lunchtime on Saturday, most people had already switched off. Moved on. Half the nation is off having a blast this bank holiday weekend, especially as it’s leading into a half-term holiday. Any entertainment the presidential election offered is done. Catherine’s on her way to the Áras, and Heather is wishing her well and posing with her grandchild.

People who had the temerity to offer themselves earlier have either been forgotten already or reduced to symbolic trivialities like the handbag and the white chinos. People who didn’t get the chance they wanted — like Billy Kelleher — are flying, their image greatly improved by rejection.

The oddity is that Kelleher and the others who didn’t get on the ballot paper should be thanking their lucky stars to have avoided the free-floating contempt that characterises presidential campaigns. The former Met Éireann woman got out so early and so quickly that she escaped that contempt. Gavin didn’t. That’s his tragedy and his family’s tragedy, and the constant references to his name as the count went on must have been painful to him and his.

Once a candidate wins, the political parties on the losing side move seamlessly on to gossip and condemnation. So Fianna Fáil starts manoeuvres to get Jim O’Callaghan the top job.

Over in Fine Gael, the initial tragedy was of Mairead McGuinness ending her contention. A formidable figure, McGuinness could work a room like the pro she was and was a confident media performer. She had, according to the grapevine, her own team ready to go. Then illness struck and she was out.

Frances Fitzgerald rejected the flattery of being told she had to run, that she was a cert, and that rejection helped her dodge a bullet the size of a cannonball, which cannonball ended up making bits of Heather Humphreys.

Sinn Féin’s fingerprints were all over Connolly’s campaign. It didn’t just beat Humphreys — it beat media, too. One of the most significant indicators of that came early, when a question about the Éirígí hire was asked, doorstep-fashion, out in the street. In unison, from those around the candidate, came the instruction: “Don’t answer the question, don’t answer the question.” She didn’t.

The missing connection here resides in media thinking first of media and getting ratty because their questions weren’t being answered. But the important people here were the voters, and journalists lost sight of that. A candidate not answering a question, the way media saw it, carried negative implications for that candidate. The voters wouldn’t like it.

This belief might be worth re-examination, since the evidence suggests that the voters didn’t think along those lines. They saw it as the usual joust between media and politician — and media failed to present them with a reason to believe otherwise.

After any election, less successful political parties commit to analysing what happened and learning from it. This time around, for Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, that analysis is pivotal, if their political presence is to continue past the end of this Government.