Mick Clifford: Joe Brolly opened a dam of pent-up grievance

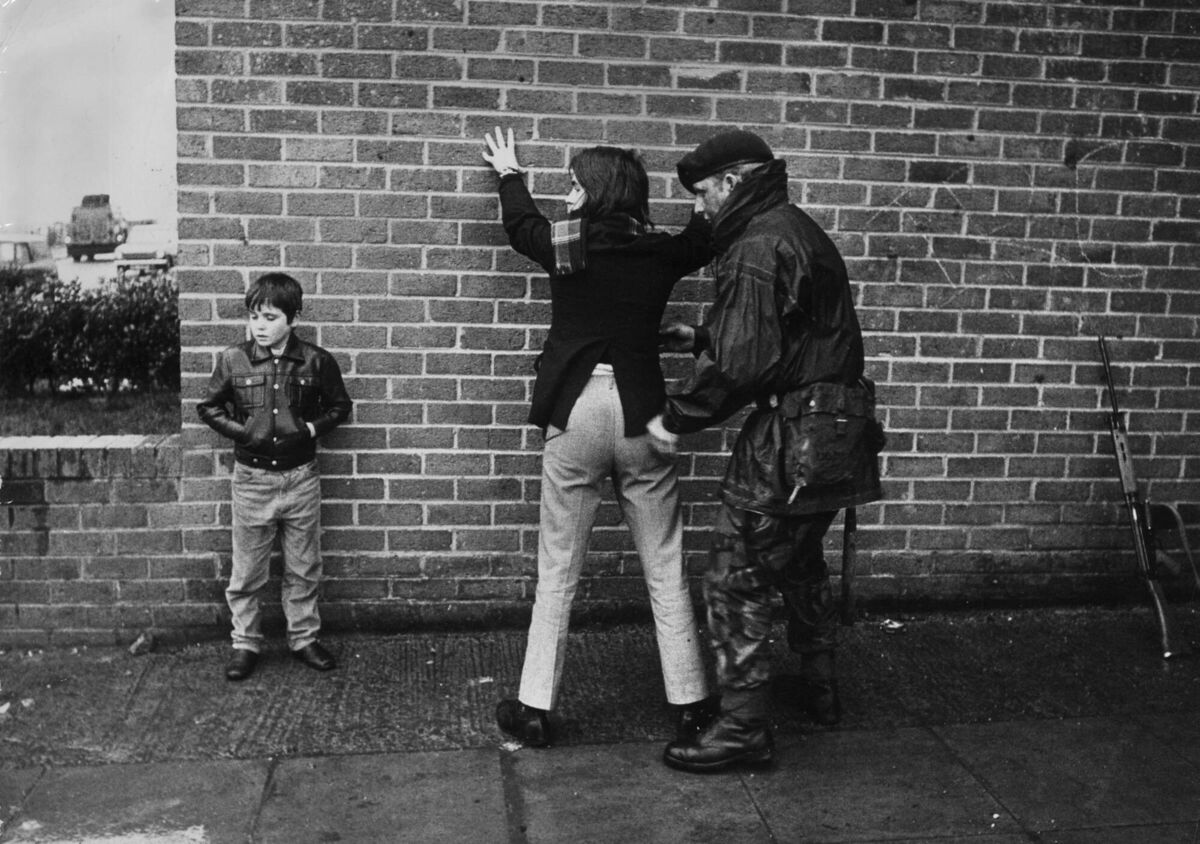

Joe Brolly said he was taken aback by attitudes towards Northerners like himself when he arrived in Trinity College during the 80s. Picture: INPHO/Lorcan Doherty

How horrible were Southerners to their Northern sisters and brothers during the Troubles? Really horrible, according to some people.

Attitudes down here towards those who crossed the border in search of work or study during the years of violence might not appear to be a big deal, but maybe it is. In the current milieu, where the prospect of a new, possibly single-entity Ireland looms, the issue might need to be addressed.

There is an acceptance that healing between the two communities in the North would be required in any new Ireland. What is less discussed is whether those of us in this jurisdiction need to examine if we were sufficiently empathetic to nationalists who came here during those years. The issue broke into the public square just before Christmas when Joe Brolly appeared in a promo for an extended interview he gave to Virgin Media TV.

In the clip, Brolly spoke of coming south to attend Trinity College in the late 80s. There, he was taken aback by attitudes towards Northerners like himself.

“You saw this whole orthodoxy started in the South that really ... it was the Catholics and the nationalists who were to blame for what happened ... If they had just behaved themselves and not worried about civil rights, and not taken to the gun that everything would’ve been fine.”

An orthodoxy, according to the , is “an idea or view that is generally accepted”.

Brolly is a lawyer, a class of people for whom precise language is an occupational tool. Yet here he was, relating that a large swathe of people in the Republic were so hostile to nationalists, so discommoded that killing and dying just up the road was interfering with their lives, that they wished those northern Catholics had continued to subjugate themselves in a sectarian state and everything would have been just fine.

Does anybody who was above the age of reason in the 1980s recognise such an allegedly widely held view? I know absolutely nobody who does, and I am quite sure that no such orthodoxy existed. I haven’t a clue if some clown one night drunkenly pointed at Brolly in the hallowed environs of Trinity and blamed him for everything, but that wouldn’t make it a widely held view.

On social media, myself and others who speak with southern accents challenged Brolly’s thesis. He was effectively painting us as harbouring what I would consider a contemptible attitude towards a community of people who, at the very least, were entitled to empathy.

Whatever shortcomings those of us in the Republic were responsible for in those years, we were not of such low morals that we considered northern nationalists a mere irritant.

What occurred next was really revelatory. An avalanche of outrage blew across social media in support of Brolly. How dare anybody question the “lived experience” of a Northerner down south during those years, went the general theme. To disbelieve or challenge his assertions was to engage in “gaslighting a whole community”, as one individual kept repeating.

The avalanche was not confined to the usual collection of clowns and cowards who feed off anger on Twitter. Serious, moderate people with genuinely held views rushed to Brolly’s defence, including writers, journalists, and academics from the North.

Many accounts referenced feelings of alienation when they came south. They mentioned apathy and ignorance here about what was going on just up the road. They spoke of attitudes towards them in which they were made to feel less Irish than those from the Republic. A lot of this is not new, but perhaps there has been an absence of any forum in which such feelings could be aired.

Was there apathy in the Republic? There is a case to be made to that effect. If so, was it attributable to the longevity of the violence or is it just the nature of things, then and now? How did any apathy manifest itself in attitudes to those who moved down here?

Was there, as some Northerners expressed in the above outpouring, hostility towards them? How widespread was it? If southerners were not, as appears to be the charge, sufficiently empathetic, then why was that so? Do such attitudes persist today?

Central to various relations and attitudes at the time was the violence. A number of those who took to social media referenced that they felt they were regarded as being somehow complicit with the actions of the Provos when they came here. This is certainly an area that deserves exploration.

Those who supported the violence propagate a false narrative that the Provos defended the nationalist community.

The protection rackets and robberies engaged in by the Provos to finance the killing was targeted at those they claim to have been defending.

If people were unfairly tarnished with the label of fellow travellers on any kind of a scale, that also needs examining, as does any perceived conflation between pursuing civil rights and killing in the name of a united Ireland.

Such exploration of the past should be done honestly and in good faith and outside the political realm. But it can’t be a question of one side, on the basis that it feels it was victimised, determining that it, and it alone, has a monopoly on remembering exactly how things were.

By last weekend, Brolly appeared to row back from his previous comments. In his column, he went into detail of how successive governments in the Republic had a repressive instinct towards anything even vaguely associated with Northern violence in the 70s. That’s pretty accurate and largely attributable to the state of siege — paranoia even — felt among the political class about the threat of the Provos at the time. But what of the orthodoxy that so many of his kindred spirits had endorsed?

“The people of the Republic had and have an emotional connection to us,” he wrote.

So there was no orthodoxy. There was no lived experience to that effect, unless it was at the hands of “the establishment”, however that might have come about.

There was no widespread contempt towards nationalists, as inferred by his initial comments.

Brolly had been talking through his hat, but his little rant has given rise to something that would be best dealt with as we all try to look ahead towards some kind of new Ireland.