Not just hanging baskets and litter: Former Tidy Towns judge on what makes a winner

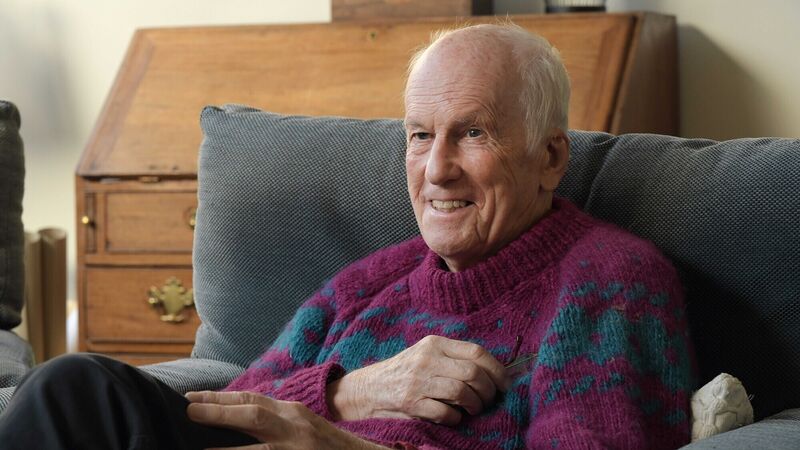

Christopher Fitz-Simon spent 27 years as a Tidy Towns judge, beginning in 1991. Picture: Moya Nolan

For three months of the year, they walk among us. Silent as spies, they scour our streets, peer into our parks, and dodge hanging baskets, undetected and unknown, the most unsocial of influencers.

"Watch, therefore, for ye know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Supervalu Tidy Town Judges cometh,” entrants are warned. Yea, though they may walk through the Valley of Dreariness, no filthy frappuccino cup shall they fear.

Occupying the exalted space between a school principal and the second coming, the Tidy Towns adjudicators roam our cherished heartlands every June, July, and August, sizing up our community spirit, our get up and go, our dedication as responsible citizens to bettering the world around us.

It is given unto few to know the mysteries of the judges’ powerful ruminations. Their final reports are anticipated with the dread of a murder trial verdict.

Over 1,000 local committees and their 30,000-strong army of volunteers spend sleepless nights tossing and turning, tormented by thoughts of rusty bikes and unpainted gates.

Having reached the promised land after decades of digging and planting, the winners bask in the limelight at an annual awards ceremony graced by Rural and Community Development Minister Heather Humphreys.

“Everyone has their favourite jobs. This is mine,” she revealed at this year’s event in October, which saw Abbeyleix in Co Laois crowned overall winners of the 2023 competition.

While the triumphant revel in their glory, the judges melt back into the shadows for another year, their identities guarded with witness protection programme levels of secrecy.

As all nature (and flowerbeds) abhor a vacuum, we are left to imagine stern officials sneering over clipboards, tut tutting unkempt entrances, broken signs and ripping pollinator plans apart with gusto.

Not so, says the country’s first Tidy Towns judge to break cover.

“That is the great thing about the competition. All the judges want the places to succeed. They aren’t writing critical notes because they’ve seen something horrible. They mention something that needs to be attended to, but they’re not looking for criticism — they’re looking to encourage,” insists Christopher Fitz-Simon.

He has agreed to speak to the and we meet, but of course, in the calm confines of the National Gallery of Ireland, where he has his eye on some Laverys.

Almost 90, Fitz-Simon spent 27 years as a judge for the competition, beginning in 1991. He knows every county in Ireland and there is not a town or village he hasn’t visited. He started what he calls his “sub-career” in his late 50s and only gave it up five years ago, he loved it that much.

He would allot six weeks every summer to judging a county, sometimes even two or three counties. He would research the places entered first, read all the submissions from the different towns, then do the judging round which he “could do very quickly”, before finally writing up and sending in his report.

Comparisons between towns were “odious” but “very necessary”, says Fitz-Simon, to help judges gauge standards, see what worked here and what didn’t work there. There were certain places where he could clearly see they could be successful if “they do this, that and that”.

“I’ve encouraged them very much in what I think needed to be done in my reports and to my great pleasure, some of them have come out a few years later as the top town in Ireland,” he says.

It’s not bad, as summer jobs go. The judges are paid a fee and have their travel and accommodation expenses paid for.

New adjudicators attend a rigorous training course, followed annually by a two-day refresher course where they are addressed by experts on birdlife, street lighting, tree planting, historic graveyard restoration, and other key aspects of the judging process.

In his first year of judging, Mr Fitz-Simon was sent to Malin, Co Donegal, and was very impressed. He shared his impressions at the judges’ meeting, telling them he “had seen the most wonderful village”.

His instincts were proved right — Malin won the best village in Ireland that year. It would happen to him several times again that he would have judged a town that eventually turned out to be a winner. From then on, Fitz-Simon was “absolutely hooked”.

Did any county stand out?

“Co Monaghan is a huge favourite of mine but the best county for winning, in general, is Cork,” he reveals. It has the most entries and gets higher marks on average than all other counties. Fitz-Simon puts this down to the generosity of community spirit in the rebel county.

Long before Leo stood on the steps in Washington DC in 2020 to urge us all to play our part, 62 years before in fact, entrants to the national Tidy Towns competition were already doing it with the Irish spirit of ‘Meitheal’ and Cork was one of the earliest entrants.

It is thanks to Fitz-Simon that Cork has three separate divisions for the Tidy Towns Competition, North Cork, South Cork and West Cork, due to the number of entrants every year.

“There was great community spirit in Cork, in the towns that have a committee. Places that have natural beauty, like Kinsale, you might think have an advantage. When you walk into Kinsale and you say ‘oh my God isn’t this amazing', but what you’re judging is what they have done to enhance it and make it pleasant for the residents and for visitors,” he explains.

Fitz-Simon is careful to differentiate between his personal opinions and his professional views when judging towns. While he freely admits Ballincollig is “not a place I would want to live”, he has previously awarded it as best Irish town.

“It’s not a personal thing,” he stresses. He remembers the first time he saw Ballincollig — which scooped the award for Ireland’s Tidiest Large Urban Centre this year — it was a “one-sided village with a big high wall along the other side” .

He wondered what was behind the wall ± a huge decaying British Army barracks. The local authority and the local people took it upon themselves some years ago to demolish the wall and revealed an ancient view of the woods down to the river Lee and its stunning bridge.

Today, there are 18th- and 19th-century squares and military buildings all restored and turned into smart apartments, a library and some “very handsome shops”.

“It is wonderful. You have the old and the new and the natural and the creatives all happening in the same place with great enthusiasm.

"Ballincollig is extraordinary with their community spirit and the number of people involved. They are always adding new things and including the schools so that they all love being part of the Tidy Towns effort,” he says.

His favourite location in Ireland is different from the towns he awarded the best prizes to, however. If he didn’t have to live in Dublin, Fitz-Simon knows exactly where he would choose.

“Cobh is where I would really love to live,” he smiles. The seaside town won his heart “because of the way it looks out on the world, to the sea, through the houses building up to the wonderful cathedral, the beautifully curved streets, I mean, it’s one of the top places and I would say will very soon win the major award,” he says.

On the other side of the coin, Fitz-Simon instantly knows if a town or village doesn’t enter the Tidy Towns competition, and doesn’t hold back.

“You know it when you see it,” he says, lamenting his childhood town of Newbliss (which turns out to be something of a misnomer).

“In my native county of Monaghan, where I've judged quite a lot, the place I know best, the village of Newbliss, clearly does not enter. It's very dreary,” he tells this newspaper.

Newbliss, as it happens, is just 3.7km away from Aghabog, the hometown of Heather Humphreys, whose department has oversight of the Tidy Towns.

Belfast, the city of his birth, falls short of his expectations also.

“Having been born in Belfast and having revisited Belfast a lot, I worked a lot for the BBC and I thought no two cities in any country could be more different in spirit than Belfast and Cork.

The key to a town’s success or not seems to be acting on the judges’ recommendations, that and the willpower of the locals.

“The days of hanging baskets and window boxes are long gone,” declared secretary of Abbeyleix TidyTowns Mary White after their recent win. Fitz-Simon agrees and is quick to dismiss commonly held notions that the competition is “about hanging baskets and picking up litter”.

“Well, at the very beginning 50 years ago it was but now it's much more environmental,” he says.

The media are not let off scot-free here either: “Unfortunately, the media and particularly television, when they're dealing with the Tidy Towns in the summer, it's very easy for them to take a snap of a pot of geraniums and forget the wonderful cathedral behind.

"So, the public think it's about that, but it's actually about that,” he says, pointing to an imaginary cathedral behind us.

SuperValu and the Government have invested millions in the competition over the years. On average, there are over 300 prizes given out each year, with about €230,000 of the total prize fund of €300,000 awarded under the main competitions.

What makes a good judge?

“You have to be terribly interested in the relationship between the natural and the manmade environment,” he replies enthusiastically. As a child growing up in Monaghan, Fitz-Simon loved maps and whenever he came to a new town, he would always look to see what the church looked like and what sort of houses were there.

Would he recommend it as a job?

“Yes. Provided you have an enthusiasm and provided you take note of what is said in the training days before each summer. You must have a visual sense. To have a love for the townscape is the thing. And wanting it to be good,” he says firmly.

Was he ever rumbled?

“I was discovered once when I stopped my car outside a local parish hall or something at a park and got out my notes,” he says, smiling at the memory.

“Out of a bush stepped a man. And he said, ‘Are you the Tidy Towns adjudicator?’ And I said, ‘I'm so taken aback, I have to tell you that I am'.”

And then he politely told him to go away.

Judging for Tidy Towns was natural progression for Fitz-Simon, who enjoyed an illustrious media career beforehand — that eye for the aesthetics led him first to the stage and then on to television where he found himself directing the first ever broadcast of RTÉ on December 31, 1961.

“I think I must be the only person still living who worked on the opening night of television,” he says.

That night, he directed the late great stage actor and original Irish anchorman Charles Mitchell on the first broadcast of RTÉ news. Both men had acted together on stage at the Gate Theatre in the 50s, with the young student Fitz-Simon merely “walking on in plays and saying four lines”, while Mitchell was the leading actor.

Imagine his horror then, when RTÉ invited the then trainee TV director Fitz-Simon to interview a candidate for the primetime newsreader for television (they seemed to think only one was needed).

“I was told a man called Mitchell is coming. And in walked Charles. And I thought, goodness, what can he think of this young person [who was walking on stage] asking him questions about his career? Very embarrassing. Anyway, when he'd gone, I said, Charles Mitchell will do the job and will speak well,” he says.

Fitz-Simon went on to direct TV serial, a precursor to , several adaptations of stage plays and a six-part documentary series in the 70s called , which allowed him to indulge his interest in the relationship between the natural and the man-made environment. It was filmed in the open air, visiting places around the country — a training of sorts for his later career with the Tidy Towns.

He also wrote more than 90 drama scripts for the BBC, including the hugely popular satirical radio comedy based in a fictional town in Donegal in the 1950s.

“It was very good because I could call the fictional hotel The Muckish Arms, you know, that kind of thing,” he says. And he’s still creating — he has two works currently waiting for publishers.

It's time to go and the leaves Fitz-Simon sitting serenely in the gallery. One last glance back and he is suddenly gone. Vanished into the crowds. The only surprise is that he was ever rumbled at all.