A visit to all eight of Ireland's National Parks

Páirceanna Náisiúnta: A visit to each of Ireland's National Parks and a look at their plans for the future

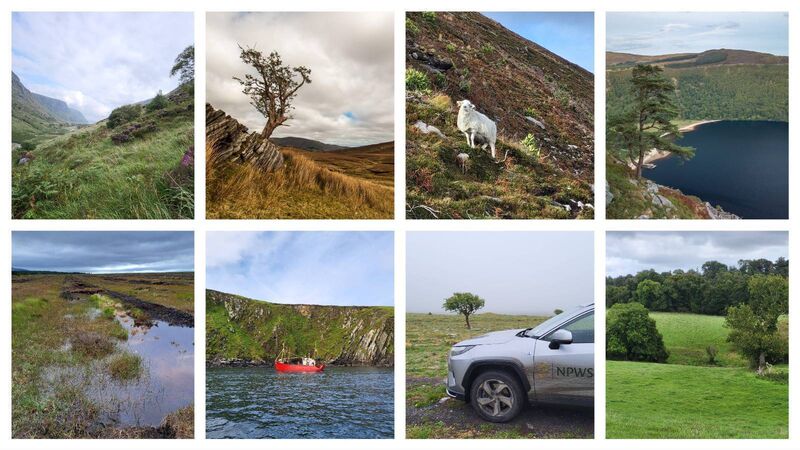

Over the past year I have visited all eight of Ireland’s National Parks in the company of the people who run them on behalf of the public: the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). It was a repeat of a tour I did in 2015-2016 when I was researching my book , at a time when there were only six.

At that time, I found a universal state of neglect and abandonment: repeated fires in Wicklow Mountains, runaway grazing and rhododendron infestation in Killarney, barren hills in Glenveagh and Connemara and promises waiting to be fulfilled in Wild Nephin. Only in the Burren was there any proactive initiative delivering outcomes for nature.

It is a sign of how far we have come that in the intervening years not only have we expanded our National Park network but at seven out of the eight I was met with an energy and level of activity that can only inspire hope for the future. Parks are expanding, invasive species are being tackled, staff numbers are up, and the NPWS is displaying a level of confidence in their role as guardians of these special places that we had not seen before. The Parks are special not least because, in the government’s own words, they “are at the heart of our efforts to protect nature”.

- Burren, County Clare

- Connemara, County Galway

- Glenveagh, County Donegal

- Páirc Náisiúnta na Mara, Ciarraí, County Kerry

- Killarney, County Kerry

- Wicklow Mountains, Wicklow

- Wild Nephin, County Mayo

- Boyne Valley, County Meath

This optimism is down to the re-booting of the NPWS under the last government, and especially then-minister of state Malcolm Noonan, which has brought vastly improved finances as well as political recognition for the importance of their role that had not been previously acknowledged.

Our National Parks are popular, 5.5 million people visited one last year, and so play an important role in the rural economy. They are entirely in public hands and so the State has a freedom to do things that are harder on lands owned by farmers or state bodies with commercial remits. However, despite all the positives of recent years, all is not rosy.

First and foremost is the lack of supporting legislation for National Parks, something that was promised in Ireland’s first National Biodiversity Action Plan in 2002. In the absence of legislation, we have no definition of what a National Park should be, how it should be managed or funded.

Repeated promises over the last 20 years have all failed to deliver. In a parliamentary question from Fine Gael TD Emer Currie in July, James Browne, the minister with responsibility for the NPWS, said that passing legislation was a “priority” for the government and that “the NPWS is currently assessing the requirements of such legislation and is considering how best to advance the process”. The snail’s pace of this work suggests that in reality it is far from being a government priority.

The lack of legislation means that our National Parks are not managed. Yes, seven of the eight have staff that are dedicated to day-to-day business however this is not done to any plan with a framework for monitoring and delivery. Priorities are set by the person who happens to be in charge and there are no mechanisms for reporting or accountability.

While on my travels, the NPWS staff I met with were open, honest and eager to discuss the issues, but to the outside world the running of the Parks is a black box. This leads to suspicion, for example in Killarney where many people I spoke to did not believe that the NPWS were tackling rhododendron in accordance with best practice methodologies. The production of management plans is just another promise that keeps being made and keeps being broken.

A lack of structure leads to a level of fantasy in the messaging from the NPWS. Statements that various Parks provide glimpses of ‘unspoilt wilderness’ or are managed in accordance with international standards to preserve ‘large-scale natural processes’ is needless greenwashing. The worst example is the newest, Páirc Náisiúnta na Mara in Kerry, which the NPWS promise will be “a truly world class National Park” when, over a year since it was announced, it has no staff, no powers to limit harmful fishing activity in the marine and continues to see mechanical peat extraction and severe overgrazing by sheep.

This points to a fear that the reform of the NPWS is not progressing as had been hoped and at a number of stops frustration was expressed at continued failures of staff recruitment. Does this signal a diminishing of political support? This would be disastrous and would see much of the good work in recent years undone. The new minister of State with responsibility for biodiversity, Fianna Fáil’s Christopher O’Sullivan, is a strong advocate of nature, but there is little evidence his government colleagues share his enthusiasm.

While there are signs that invasive species are being brought under control, a common feature of all Parks is the excessive level of grazing, from sheep, goats and deer, that is preventing the emergence of dynamic ecosystems. Worrying, not all Parks recognise this as a threat although in Glenveagh a flagship rewilding initiative is underway that could have a nationwide influence. Another commonality is the lack of baseline ecological data that is needed to inform good decisions. Basic information, like up-to-date habitat maps, are lacking.

Our National Parks therefore are failing to deliver. It was wonderful to spend the past year seeing the action on the ground and speaking to the great staff at the NPWS but we need a gear change if these places are to meet their potential.