Paul Rouse: GAA must do more to stand against cowards who claim the tricolour for exclusion

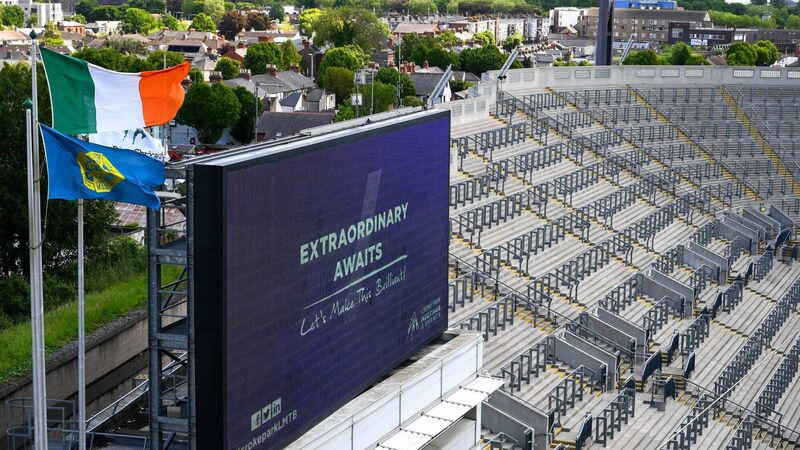

Flags flutter in the wind beside Hill 16 before a championship game this summer. Pic: Ray McManus/Sportsfile

There is no surprise in the news that the GAA is again moving to amend a rule which says that the gear worn by its players is “of Irish manufacture”.

Rule 1.14 currently reads: “All jerseys, shorts, stockings, tracksuits (tops and bottoms) and kitbags, worn and/or used for official matches, in pre-match or post-match television or video interviews, player walk-ups and photographs, shall be of Irish manufacture. This requirement shall also apply to replica playing gear.” The idea that this rule exposes the GAA to a multi-million euro fine under EU competition law is not a new one and the proposed amendment would see the words “of Irish manufacture” replaced with “manufactured by a GAA licensed kit manufacturer”.

The precise wording of the rule builds on Rule 1.1 in the “Aims and Ethos” section of the Official Guide, which states: “The Association shall use all practical endeavours to support Irish Industry especially in relation to the provision of trophies and playing gear and equipment.” Earlier this week, John Fogarty reported in these pages that the GAA was finalising its list of kit manufacturer licensees and those companies were being informed of a duty to be able to provide jerseys within seven to 10 days of an order being made. The logic of this appears to be that it would facilitate “companies having the production means on this island.” It will be exceptionally difficult to both monitor and enforce this in practice.

The connection between the use of Irish manufactured goods and the GAA runs to the years even before the Association was even conceived. Before he founded the GAA, Michael Cusack had been a cricketer and a rugby player, but one of the things that changed his approach to sport was an Industrial Exhibition of Irish-made goods in 1882. Along with language revival and the publication of books of Irish history and mythology, this chimed with the potential for a new economic future for Ireland.

Sport – in Cusack’s conception – was to be part of a swell which would promote ideas of Irishness, as an alternative to the power and prestige of the British Empire. He said this in a newspaper column which he wrote every week in the early 1880s.

Cusack also wrote about the importance of Irish industry in a newspaper he started himself in 1887 and in that year the Central Council of the GAA ordered that the medals for the first All-Ireland championships in football, hurling and athletics should be made in Ireland.

J. F. O’Crowley from Cork was asked to procure them in gold and silver, but this proved problematic as sourcing quality medals in Ireland proved difficult. The medals for the 1887 hurling champions were eventually presented in 1913.

The desire to use Irish goods (as well as to conduct business in the Irish language) was repeatedly expressed by the GAA in its official documentation and in the speeches by its officials at various meetings.

There is no doubting the sincerity of those ambitions, but it proved a difficult task.

The change now proposed to the Official Guide is a reflection of the extent to which the economic context in Ireland has been transformed.

Every working constitution of every sporting organisation is an uneasy manifestation of historical experience, present realities and attempts to imagine the future.

The reality of the GAA’s Official Guide is that it is almost entirely consumed with the practical operation of a modern sporting organisation. It could not be otherwise. So it is that the rules of the Association are spelled out in the sort of minute detail in everything from disciplinary procedures to membership and affiliation processes. The current success of the GAA is rooted in the smooth and proper operation of all of these rules.

But the shadow cast by history is a real one For example, the GAA commits itself to “actively support the Irish language, traditional Irish dancing, music, song, and other aspects of national culture.” There are precise rules around the use of Irish in official documentation, and the flying of the flag and anthem (hurlers must remove their helmets, for example).

And the GAA commits to being “non-party political” in its meetings, and anyone who infringes on this can be suspended for six months.

More than that, it pledges to “foster an awareness and love of the national ideals in the people of Ireland and assist in promoting a community spirit through its clubs.” The GAA excels at the latter, but what exactly does the first part of the sentence even mean? What are the nation ideals? Who exactly is meant by the people of Ireland?

There is also a commitment to “principles of inclusion and diversity at all levels”, and an avowed anti-racist and anti-sectarian policy.

These commitments are important and to be pursued – the question is, in what way do they fit into some imagined “national ideal”?

In the context of a society which has a significant minority who are now flying the Tricolour not as an act of patriotism but as one of exclusion, the GAA’s capacity to bind communities together is vital. The Association should be to the fore of the inclusion of immigrants into clubs and into its clubhouses. Is there not capacity to do this more successfully before Ireland descends further into the fevered cruelty of anti-immigrant rhetoric that is claiming more and more people around the world by the week?

It is a tribute to the men and women who have run the Association for more than 14 decades that they have repeatedly found ways to prosper in the face of shifting challenges.

A new one is gathering momentum in which cowards, zealots and racists are seeking to set people at each other’s throats. The most practical response to their posture is to be found in communities and in the shared space of clubs.

Jarlath Burns has spoken powerfully on the importance of inclusion and the welcome to be provided to immigrants ; the Association as a whole could do much more.