Book review: Varadkar’s overview of his time in politics carefully avoids his failings

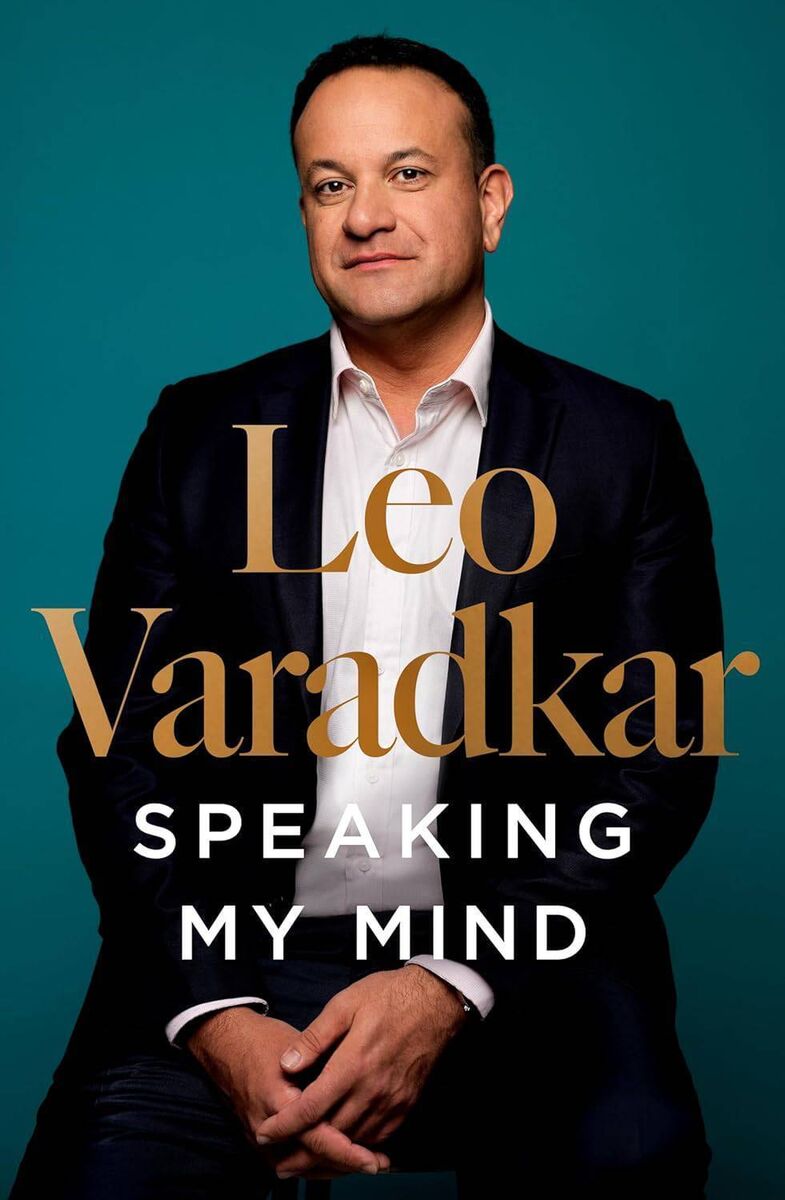

Former taoiseach Leo Varadkar’s struggles with keeping his sexuality from the public glare are detailed in ‘Speaking My Mind’, which moves through his early years and his rise in politics, to eventually reaching the apex of Ireland’s political ladder. Picture: Fran Veale/Julien Behal Photography

- Speaking My Mind

- Leo Varadkar

- Sandycove, €29.99

In the Autumn of 2014, I got a call from Leo Varadkar’s media handler. He told me the transport minister, as he then was, wanted to buy me lunch.

Varadkar was in government for 14 years, right though the beginning and ballooning of the housing crisis.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.