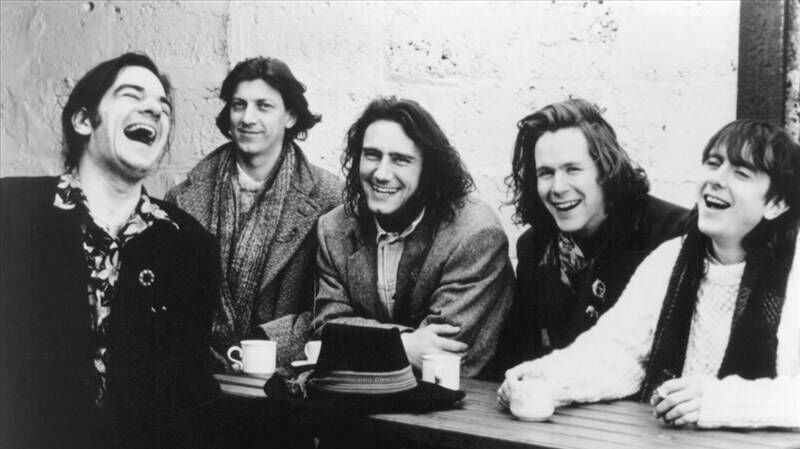

Liam Ó Maonlaí of Hothouse Flowers: 'My heroes are old men and women'

Liam Ó Maonlaí and Hothouse Flowers have upcoming gigs in Cork and Wexford.

As you might expect from someone who has been making music for nigh on half a century, Liam Ó Maonlaí knows a few things about preserving the voice; which is handy, as when I mention my child has a sore throat, Liam knows just the thing to sort it.

“Hot water bottle on the belly works for me,” he says, adding, “The throat is connected to the belly. Works for me every time.”

This type of innate, acquired knowledge and, as he explains, its Chinese medicine origins, should come as no surprise when you consider O’Maonlai’s life in music. Tousled of hair and bearded of face, he’s unlikely to swap his traditional threads for tracksuits any time soon, in the same way that he has followed the arc of traditional, folk and world music ever since he and his bandmates in the Hothouse Flowers decided that they could do without all the baggage that comes with fame.

To hear him talk about music - as craft, as vocation, as a kind of ethereal life force - is to hear someone who has leaned into both his age and the wisdom that comes with it.

“I'm just older,” the now 60-year-old says, matter-of-factly. "My heroes are old men and women. You know, my role models are the old sean-nós singers from the west. And they get better as they get more older. I remember I judged a sean-nós competition down in west Kerry, in Dhún Chaoin, and Dáidí Mhartan was the winner, and he died the next day. Sean-nós isn’t really learned - it's just the way we used to sing.”

And it should be said, Ó Maonlaí is hardly an arriviste when it comes to the living tradition. As he recalls, it was playing to the tin whistle to a high standard when he was a child that opened the way to the career which followed. “I realised I was quite good, and I realised that it could get me around - if I played well enough, I’d win this competition, and if I played well enough there, I’d get to Galway, or I’d get to Tralee or I’d get to Athlone, I’d get somewhere in Ireland, off on my own, from my own talent.”

As he puts it: “You’re given a whistle, you’re given traditional music, and you’re given a key to yourself.” And that can open other doors, not least into the world of rock music. The Hothouse Flowers, which Ó Maonlaí has fronted since the beginning, are 40 years old this year, but it was the blues/rock element of the national Slógadh competition which got them going, albeit with an earlier iteration that featured future My Bloody Valentine member Colm Ó Cíosóig, and Maria Doyle Kennedy.

"That was the blinding moment that I just said, right, I'm not pretending that I'm going to try and do college to please those who want me to go and do college,” Ó Maonlaí recalls. "I'm just doing this. I know this is going to work. When you have a good moment with the band, and it crystallises, you can see, this has its own power. And as long as I serve this, it will be served.”

Not that it was perfect from the very beginning: “The first gig was desperate. The second gig was a bit better, and then the third gig was good.”

And so it began to take off, including appearances on for and a cover of well-received albums scoring on both sides of the water, and touring galore. Yet Ó Maonlaí attributes much of that success to the band having honed its success on the streets as they busked and busked and busked. Nowadays Liam sees plenty of people still out there, but they're mic-ed up.

"And I kind of go, well, sure, but it looks like people are road-testing instead of actually doing it. If it looks like you're road-testing, or that you're trying to make money, or you're anything other than being in the heart of just doing it, in the heart of singing the song, in the heart of giving yourself to that moment that will just lift yourself out of yourself, and as a result, lift other people out of themselves... That's what my thing has been and always will be.”

It's maybe this busking and traditional music backdrop which prevented the Flowers from simply flickering and fading away. Ó Maonlaí says they realised that there was “a ruthlessness” about the music business, as in any business.

“It’s just to know that it’s there and remember that you are still living a dream. And we did seven years in that environment, and then my Dad died and I kind of said, OK, I’ve had enough of being so closely tied up to this wheel.

"I felt it was important to get out of that atmosphere. At some point I just said this isn’t the way it's going to be. I didn’t think I’d survive, but then we were playing every night and that was the dream that was being fulfilled.”

He recalls the tours of America, “three, four months on a bus… filling houses … and then being told that our part of the company wasn’t making a profit. You kind go go, OK…”

Those gruelling tours meant songs emerging from soundcheck, filling much of the band’s second and third albums. “That transmitted when there were times we couldn’t really talk to each other, we spoke to each other through music. And we’re still friends and we still walk into a room together and and we still do what we do together and we are still chasing something elusive in the music.”

The band were in Stormont, of all places, when the conversation about the initial breakup was had - “I think we didn’t even know we were going to have the conversation until we were having it.”

That parting of the ways was amicable, with the rest of the band touring extensively with Michelle Shocked and Ó Maonlaí taking on new opportunities, having previously felt like he had to turn them down. There followed solo material and, increasingly, collaborations, such as when Ó Maonlaí went to Mali in January 2006 and 2007 and played at the renowned Desert Festival with uilleann piper, Paddy Keenan, moments captured in a subsequently acclaimed documentary.

In early 2025, ahead of a Flowers tour of Ireland and the UK, he is also putting the finishing touches to an album which began back in 2018 with a Tokyo-based producer, as well as material with a Spanish-Czech musician, and more music again, this time with a woodwind musician which he believes could be movie soundtrack material. Add in his radio show, on RnaG, and his schedule is pretty packed. Just as well he's minding the voice.

He laughs when asked what it was like to be a sex symbol. "I don't know, what is a sex symbol," he says. "Like, somebody who wears a see-through bra?

"Certainly, yeah, I was a shy kid, and I felt, well, you know, this might present me in a way that will bypass my shyness when it comes to romance. And it wasn't as simple as that, for sure, but it was interesting to struck a chord on that level, I suppose. The thing is, when you're so busy, there's no time, there's no time. And actually you don't meet people after gigs, because there's a there's a kind the survival of the fittest, and people who want to come and have an autograph or even to chat with the band. So it doesn't really happen, you know."

But the power of music endures in pretty much every other way. "Well, you might, you might be going through the worst time of your life, and you pick up a CD that you haven't listened to yet, but you bought and you thought, I'm going to listen to that. And you put the CD on, and it fixes your heart. It doesn't make you better, but it fixes the pain and gives you that's the stuff that was written about the Fiana that you know, that somebody could sing a song and a whole army would sleep.

“ That's only a step more dramatic than what actually is available still. You know, a mother can still sing a child to sleep, and a song can still take a person out of depression. A song can save a life.

"I just feel there's good music to be made, and I’m going to make it."

- Upcoming gigs by the Hothouse Flowers include March 14, Cork Opera House; March 15, National Opera House, Wexford

"I think traditional music is fantastic because it's everywhere in Ireland and it actually doesn't care whether it gets the spotlight or not. It has been enjoying the spotlight in different ways, Lankum being a prime example of the use of the drone and the murder ballad. Lankum are serious. They are traditional musicians, they're collectors, they're scholars, which is what a traditional musician is. They collect.

"Traditional music blazes away, regardless of the spotlight. And that's what excites me the most. You know that there's people who will never go on the stage, but those who do go on the stage will travel and take Friday off so that they can go and play with this person, down in their local in wherever it might be, Toomevara or Tulla or Clon or anywhere, to go to sit beside that person who only plays on a Thursday night in their local. That's older than the business. That's older than houses and villages and cities that we have. And it’s still brand new.

"If you're plugged into roots music anywhere in the world, you'll always have a bed, you'll always have a table to sit at, and you will sit with the wildest and the meekest at the same table. There’s no differentiation when the tune has been played. That's an ongoing spirit.

"I remember singing a bilingual in Wembley Arena: Full house, our gig, and pure silence. You know, speaking an Irish language, Wembley Arena, and there being a pure silence. I thought, wow, but I didn't doubt that. At the same time, it's looking back, I go, wow. But I mean, the thing is, what we fought for, what our people fought for, wasn't a flag, it was a way of life that was good, and the music represented a good way of life.

"The Gaeltacht is precious,” he says. “There’s a consciousness there of the Irish person, the Irish mind that hasn’t been interfered with.

"When you have a people and their language has been removed that’s a very strong thing. To reclaim the language is vital. And it’s exciting to see what is happening in Belfast, it’s the fastest growing Gaeltacht in Ireland. Language is more delicate than music is, funnily enough. Although you can always tell an Irish speaker in the way they play, it’s a subtle thing and I can’t even explain it."