Irish artists pick their favourite piece at the Crawford Gallery in Cork

Dorothy Cross and Tom Climent are among the artists picking their favourite piece at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork.

Dorothy Cross is one of Ireland’s best-known conceptual artists. In a multi-faceted career, she has used materials as diverse as a human heart, cowhides and taxidermied sharks to create works that are sometimes unsettling but always highly original.

Cross’s favourite work in the Crawford Collection is a pair of wood carvings - An Arm Showing Muscles and A Hand and an Arm - produced by John Hogan (1800-1858) around 1820. Hogan was from Tallow, Co Waterford. As a young man, he worked full-time at the Crawford, carving studies of hands, legs and feet, before moving to Rome, where he had a successful career as an artist.

“It may seem like a weird choice,” says Cross, “but I’m fascinated by his carvings. They’re such physically beautiful objects.” Cross spent a year studying at the Crawford College of Art, at a time when it was still housed in the premises of the Crawford Art Gallery, before going on to graduate from the Leicester Polytechnic in the UK and the San Francisco Art Institute in California.

“At the Crawford, we’d be dragged into the sculpture gallery to draw the Belvedere Torso or whatever,” she says. “The drawing was always of classical sculpture. But I remember how I’d encounter Hogan’s carvings in a glass cabinet on the second storey every time I walked up the back stairs.

“I assume they had a medical purpose originally, and were made to show the musculature and bones.” Crawford included Hogan’s carvings, along with dozens of other artworks and objects from the National Collection, in a touring exhibition called Trove she curated in 2014. “I hung them with Fergus Martin’s abstract paintings. It was the first time they’d been shown in conjunction with anything else.” Cross admits they may well have influenced some of her own work; among her pieces in the Crawford Collection is Right Ball and Left Ball, a bronze sculpture featuring casts of human hands.

Like Cross, the West Cork-based sculptor Vivienne Roche studied at Crawford College of Art when it was based at the Crawford Art Gallery.

“To this day, my favourite work in the collection is a piece I saw every day as a student; Joseph Higgins’ An Strachaire Fir,” she says. “That, and another sculpture of Higgins’ called A Toiler of the Sea, were on either side of the entrance to the gallery upstairs. In those days, you could still touch the artworks in public galleries, and An Strachaire Fir was quite literally a touchstone for me.”

Higgins was born in Ballincollig in 1885, and attended Crawford School of Art as a night student. He died young, of tuberculosis, and only nineteen of his sculptures survive.

“Higgins would have worked in clay, and cast An Strachaire Fir in plaster,” says Roche. “It’s superbly modelled, but it was only after his death that his son-in-law, the sculptor Séamus Murphy, had it cast in bronze.”

While studying at the Crawford, Roche was taught modelling from life by the late John Burke. “He held Higgins in very high regard, and would have had us look closely at his sculptures. Studying Higgins’ work was a great help to me in my learning.”

In 2015, Roche curated an exhibition of sculptures at the Crawford called Head to Head. It included Higgins’ An Strachaire Fir and a work of her own, a bronze head of her nephew, Stephen Archer. “That was very much a homage to Higgins,” she says.

Roche is currently showing at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin, in a major solo exhibition called Abridged.

Alice Maher, another Crawford College of Art graduate, works in a broad range of media, including drawing, sculpture, film and installation. Recent work has included her collaboration with Rachel Fallon on The Map, an epic textile sculpture that explores the mythology of Mary Magdalene; this is currently on show at the Irish Arts Centre in New York.

Maher’s favourite piece in the Crawford Collection is an oil painting by the contemporary Irish artist Elizabeth Cope; Generation Gap, from 2006. Cope, born in Co Kildare and now based in Co Kilkenny, is known for her sometimes provocative paintings and etchings.

“I chose Generation Gap because it contains all of Elizabeth’s wild energy and lickspittle paintwork,” says Maher. “The subject matter nods to those Death and the Maiden paintings of medieval times. Here you have the young maiden with her parents, first as sexual beings, and then as skeletons.” In Maher’s opinion, “the painting has everything; sex and death, love and parenthood, wild abandon and gentle care, all swimming in the golden soup of life. Really it is a hymn to life and at the same time a loving embrace of death.”

The Crawford College of Art had moved to its current premises on Sharman Crawford St when Michael Quane enrolled as a student in 1982. Nonetheless, he spent a great deal of time at the Crawford Art Gallery as a student.

“Myself and Charlie Mahon, the potter, worked there part-time all through college, restoring the classical casts,” he says. “We hung shows there as well. The big one I remember was an exhibition by Eduardo Paulozzi in 1985 or ’86.”

On his visits to the Crawford Art Gallery, Quane became intrigued by a sculpture by the Yugoslav artist Toma Rosandic (1878-1958), a life-sized wooden carving called Nude Male Figure that the American philanthropist Alfred Chester Beatty had donated to the institution in 1954.

“It was stuck in a corner, inside a door in the offices,” says Quane. “So it felt like a secret discovery. Most of the figures in the sculptural work I was seeing were female, and seemed voyeuristic. But this was male; almost all the figures in my own work are male or androgynous.” Quane often works in stone, and he is represented in the Crawford Collection by a limestone carving called Strange Beasts. But he has also carved wood since his early teens, which was partly what drew him to Rosandic’s figure. “Timber has great strength,” he says. “It’s a very elegant material.”

One aspect of Rosandic’s sculpture that Quane is critical of today is the drape wrapped around the figure’s leg. “Rosandic was working from one trunk of wood,” he says. “When you’re carving, there’s always a danger of the timber cracking, and he was probably being cautious. But the drape seems chunky to me now.”

Quane’s solo exhibition, Belonging, opens at the Solomon Gallery in Dublin on 26th September.

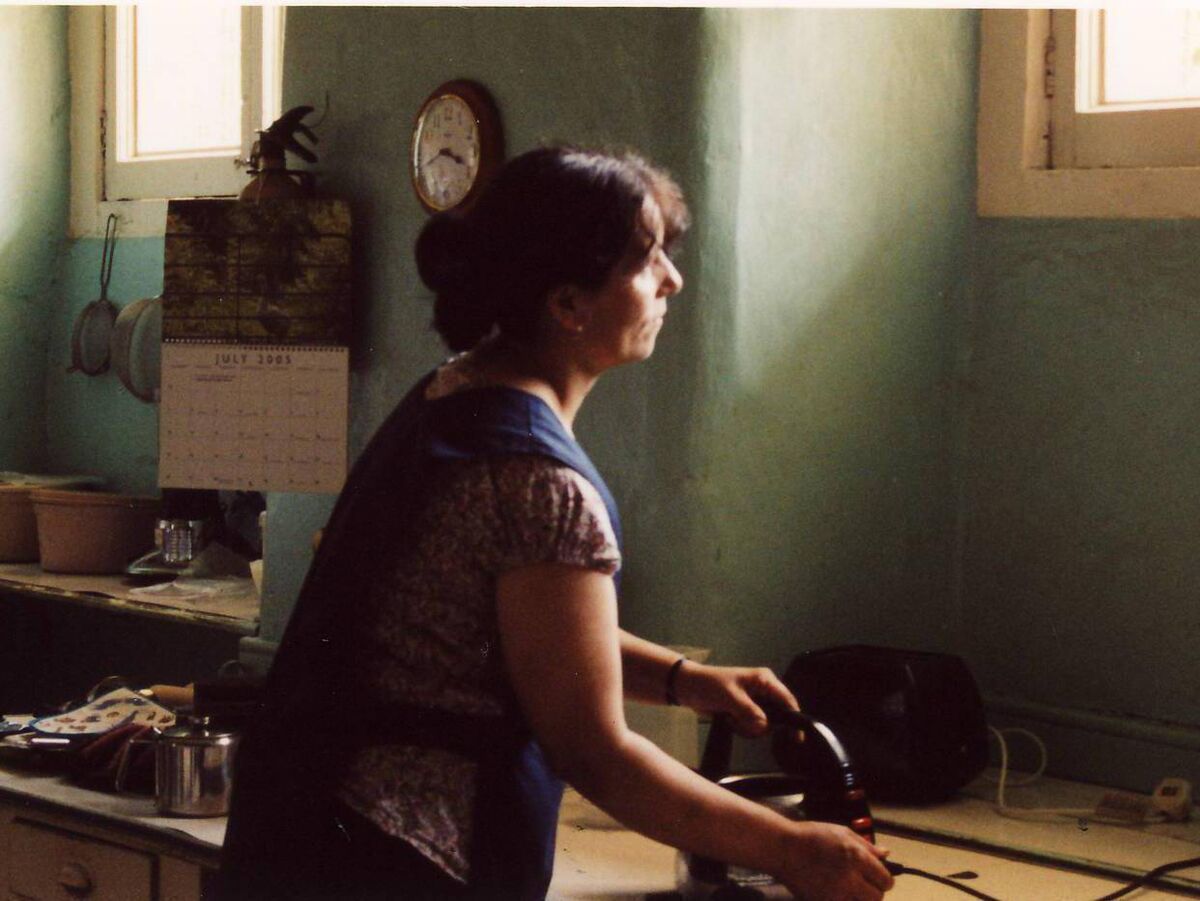

Film, drawing, sculpture, installation and performance have all featured in Aideen Barry’s numerous exhibitions here and abroad. She is represented in the Crawford Collection by the stop motion film, Not to Be Known, which examines the repetition and boredom of domestic life.

Barry’s favourite work in the Collection is also a work on film; the contemporary British artist Tacita Dean’s Presentation Sisters, produced to commission for Cork’s tenure as European City of Culture in 2005. Dean’s film was shot at the Presentation Sisters Convent on Douglas Street, and documents the daily habits of the last five nuns who lived on site.

“I’m not at all religious,” says Barry. “But Dean captured that lovely collegial relationship they had; there’s one scene in particular where the nuns are watching the All-Ireland on television, and they’re all shouting for Kerry. That’s just a beautiful moment in contemporary history.

“Presentation Sisters is a seminal film, and it had a profound effect not just on me, but on a generation of artists who went on to be filmmakers. You can see how it influenced Martin Healy’s film The Last Man, for instance, another amazing piece of work that’s also in the Crawford Collection.”

Barry studied at Galway Mayo Institute of Techology and Dun Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology, but the Crawford has been a large part of her life since early childhood. “I come from a working class background, and when we went downtown, we’d go to places where there was free access. We’d go the City Library, and then around the corner to the Crawford. That’s one thing we got right in this country, having free access to our museums and galleries.

“My mother would have brought my older sister Fiona to art classes at the Crawford when I was four or five, and I remember wandering off to look at art and being amazed by it. I don’t think I would have become an artist if it had not been for my experience of visiting the gallery from such a young age.”

Barry will represent Ireland at the Bangkok Art Biennial in October.

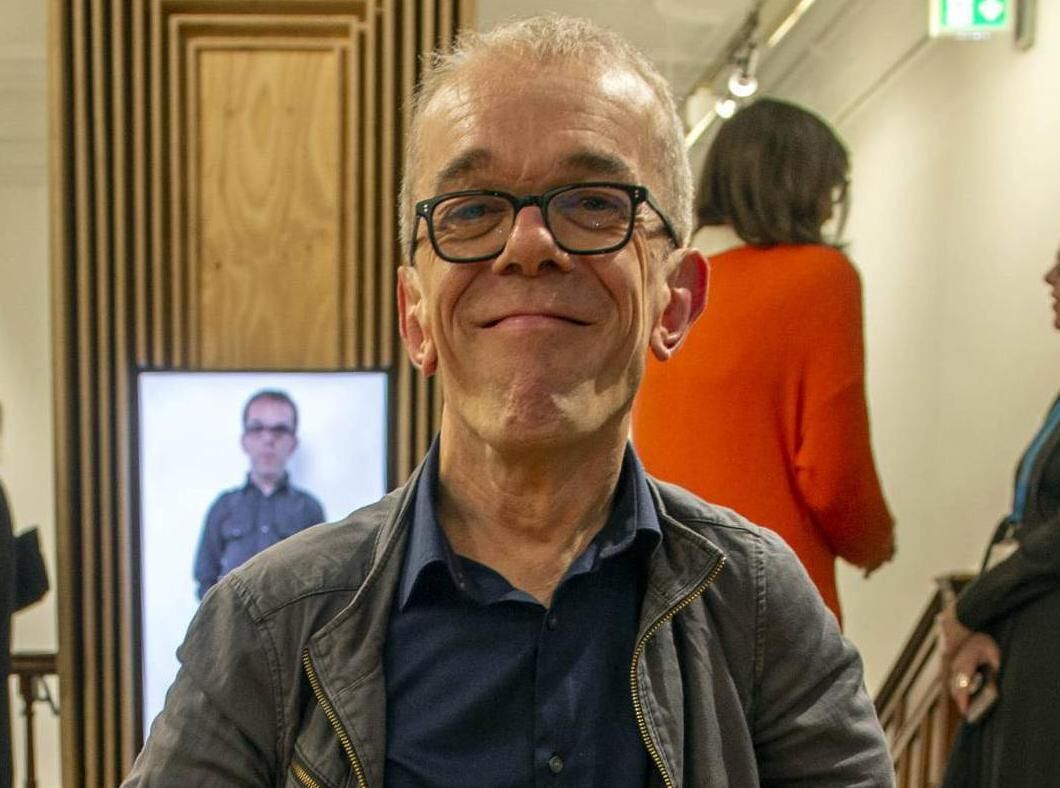

Tom Climent is represented in the Crawford Collection by a painting called Eden, a landscape of sorts that hovers somewhere between representation and abstraction.

His favourite work in the Collection is a painting that achieves a similar kind of ambiguity; Blue Still Life with Knife by William Scott (1913-1989), the Northern Irish artist best known for his domestic still life studies.

“Scott had the ability to transform everyday objects into flat abstract shapes,” says Climent. “This connection between the world around us and abstraction has echoes in my own work, and is probably why I've always responded to and admired his painting.”

Climent is a graduate of the Crawford College of Art, and visited the Crawford Art Gallery almost every weekend while a student. “I’d go around the record shops, and then I’d pop over to see what was on in the gallery,” he says.

In 2022, Blue Still Life with Knife was included in an exhibition at the Crawford called As Far As I Can See, curated by Corban Walker. Seeing it again reminded Climent of how “Scott takes the purest approach to painting; he has the ability to flatten space, and the placement of the objects on the canvas creates a tension and a connection between the objects and the ground. This makes the shape of the spaces around the objects as important to the overall composition.

“His work connects us to the everyday, using basic objects that convey a human presence. He said himself: ‘The objects I painted were the symbols of the life I knew.’"

Corban Walker is a graduate of the National College of Art & Design in Dublin. He represented Ireland at the Venice Biennale in 2011, and the Crawford Collection includes a number of his minimalist drawings.

Walker’s favourite work in the Crawford Collection is Nexus G, a painting by the Co Wicklow-born artist Cecil King (1921-1986). King, whose background was in business, was a neighbour and family friend of Walker’s in Dublin. Largely self-taught as an artist, he forged a successful career from the 1960s.

Nexus G is typical of King’s work in its balance and exactitude. "Cecil always knew where to draw a line,” says Walker. “On a canvas, he would create a structure that defied two-dimensionality. His palette had intellect; everything he painted was deliberate, precise and effective.”

King was one of the curators of the revolutionary Rosc exhibitions of international art, held in Dublin every four years or so between 1967 and 1988. “He was also instrumental in advocating for contemporary Irish art in those years,” says Walker. “At a time where there was little public funding, if any, for the visual arts, he was a dedicated and excellent fundraiser for Independent exhibitions.”

Walker included Nexus G in As Far As I Can See, the exhibition he curated at the Crawford in 2022. “The fact that Crawford Art Gallery has this painting in their collection is of major significance,” he says. “It’s an excellent example of Cecil’s succinct yet gracious humility."

- Crawford Art Gallery will close its doors on Sunday, September 22, for at least two-and-a-half years for a major renovation