Ceoltóirí Chualann: Seán Ó Riada and the band that changed the course of Irish music

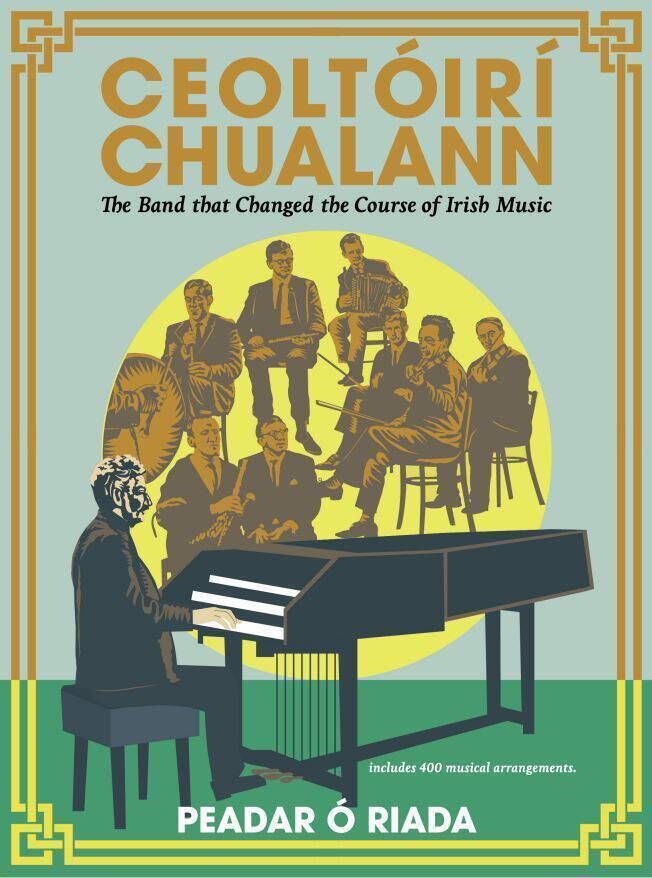

Some of the members of Ceoltóirí Chualann: Michael Tubridy, Éamon de Buitléir, John Kelly, Anthony Kelly (John’s son), Sonny Brogan with whistle, Paddy Moloney, with Seán Ó Riada behind with Ronnie McShane and Seán Potts. Picture: Courtesy of Mercier Press

“It was new; it was unique; it was exciting; it was ever-changing. It was like colour television in a time when you only saw black and white photographs in newspapers.”

Ceoltóirí Chualann were like pop stars in 1960s’ Ireland according to Peadar Ó Riada, whose composer father Seán was founder and leader of the band of Irish traditional musicians.

Such was their popularity, he says, that when their 1969 concert at Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre was announced, “the tickets went on sale at 9 o’clock in the morning and there was a queue around two thirds of the block - by quarter to 10 they were all sold”.

The release of his book Ceoltóirí Chualann – The Band That Changed the Course of Irish Music, concludes a decade of research by composer, broadcaster, and choir director Peadar, who maintains that nothing in the half-century since the band’s last performance prior to his father’s death has rivalled their originality.

“I haven’t heard anything as revolutionary in Irish music since they stopped playing,” he says. “Traditional musicians had been playing forever but they’d never played like that.”

Ceoltóirí Chualann, dressed in suits and bow ties and playing arrangements of traditional music by Mise Éire composer Seán Ó Riada, looked and sounded distinctive and elevated traditional Irish music to new levels of respectability.

The band, initially created to perform in Bryan McMahon’s The Song of the Anvil, a 1960 play for the Abbey Theatre, where Ó Riada was musical director, was officially launched the following year at the Shelbourne Hotel during Dublin Theatre Festival.

“The biggest revolution was the fact that they played like a band,” says Peadar. “People bought tickets and went in to see traditional musicians on a stage for the first time. Before that, musicians would appear at dances or parish halls.

“When Seán started out with Ceoltóirí Chualann, music wasn’t allowed in most pubs. It was regarded as something that was belonging to an age of poverty and ‘backwardness’. But Seán refused to take that and he put it up on the stage and said, ‘Now look at it, listen to it, it’s something wonderful’.”

Seán Ó Riada described on his radio series Our Musical Heritage the thinking that informed the band’s direction. An ideal type of céilí band or orchestra, he said, must have “variety – which, expressed through variation, is a keystone of traditional music”.

“It must not, therefore, flog away all the time, with all the instruments going at once, like present-day céilí bands. Ideally, it would begin by stating the basic skeleton of the tune to be played; this would then be ornamented and varied by solo instruments, or by smaller groups of solo instruments. The more variation the better, so long as it has its roots in the tradition, and serves to extend that tradition, rather than destroy it by running counter to it.”

Ó Riada, a jazz pianist as well as being classically trained, studying under Aloys Fleischmann at UCC, had an unusually good ear for combining instruments, says Peadar.

“That was part of his genius – the use of sound, as you see with Mise Éire, which grabbed the attention of the whole nation in 1959. It’s the same thing, the same genius, but he did it with a group of traditional musicians.”

Ó Riada delved into the 1792 Belfast Harp Festival music in the Edward Bunting collection to reintroduce this body of music back into the public consciousness with Ceoltóirí Chualann.

“One of his extraordinary abilities was to be able to read the old manuscripts of [George] Petrie and Bunting, who were trying to write down in two dimensions what was an aural tradition,” says Peadar.

His polyglot father was “a wonderful sight-reader and could see what they had written down and re-transpose that back to what it originally sounded like”.

Peadar recalls how Seán, aiming to recreate the sound of the wire-strung harp, played harpsichord in the band, despite the instrument’s scarcity in 1960s Ireland.

“It was always a big operation to try and get one in-situ and in tune for him to play. And if a harpsichord wasn’t available Seán would stick thumbtacks into the hammers of a piano or brown paper between the hammer and the strings. I often had to do the job for him myself as a kid.”

In addition to studio recordings, from 1961 to 1969 Ceoltóirí Chualann were the mainstay of weekly Radio Éireann programmes Reacaireacht an Riadaigh and Fleadh Cheoil an Radió, recorded live at sold-out concerts.

These programmes demanded, over their eight-year duration, vast supplies of tunes, which were carefully noted down by band members Michael Tubridy and Éamon de Buitléar (later to become a wildlife filmmaker).

Directions for 400 of these arrangements now form a central part of Peadar’s book, alongside historical narrative, examples of his father’s handwritten scores, items from the Ó Riada archives, insights from tenor Seán Ó Sé, and details of recordings and broadcasts.

In the years following Seán Ó Riada’s death in 1971, aged 40, dé Buitléar presented Peadar with two volumes of the arrangements. Tubridy later contributed his extensive notes, with Ó Sé “riding shotgun” as adviser and assistance from Ceoltóirí Chualann fiddle player Seán Keane.

Keane’s sudden passing last May was “an awful shock”, says Peadar. “About three days before he died I spent an hour on the phone with him, talking about one tune. I’m very sad that he won’t be there to see the finished work – or any of them [band musicians].”

Peadar, who directed Ceoltóirí Chualann’s occasional appearances in later years, with some original members represented by relatives, is doubtful they will perform again.

Publishing the band’s history, with arrangements in a form “anyone could access, anyone could try out”, was something Peadar felt he had to do.

“It’s one of the last duties to my father really. He’s dead 53 years and I’ve spent that time working on his stuff. I have to do a bit of work on my own as well now. I’m running out of road myself,” says Peadar, currently working towards next year’s third Féile na Laoch festival honouring his father in Cúil Aodha.

- Ceoltóirí Chualann: The Band That Changed the Course of Irish Music (Mercier €24.99) is launched by Martin Hayes, with Peadar Ó Riada and Seán Ó Sé, at a free event on Friday, April 26, 6.30pm, at Cork City Library during World Book Fest: corkworldbookfest.com

Ceoltóirí Chualann members included Michael Tubridy (flute), Seán Potts (whistle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes/whistle), Sonny Brogan (accordion), Éamon de Buitléar (accordion/bodhrán), John Kelly (fiddle), Martin Fay (fiddle), Seán Ó Riada (bodhrán/harpsichord ), Ronnie McShane (bones), Peadar Mercier (bodhrán/bones), and Seán Keane (fiddle).

Their first singer was Darach Ó Catháin, who emigrated to England. His successor Seán Ó Síocháin left on becoming GAA secretary general in 1963, handing over to fellow Corkman Seán Ó Sé.

Radio Éireann series Reacaireacht an Riadaigh inspired the band’s debut album of the same name for Gael Linn in 1961. Film soundtrack The Playboy of the Western World the same year was followed by album Ding Dong, reflecting their Fleadh Cheoil an Radió broadcasts, before Ceol na nUasal in 1967. Ceoltóirí Chualann recorded music for Richard Murphy’s ‘The Battle of Aughrim’ in 1968, before albums Ó Riada and Ó Riada sa Gaiety.

The band’s first EP was Irish language ‘pop’ hit ‘An Poc ar Buile’ which shot Ó Sé to fame and was followed by ‘Neilí’, ‘Mo Chailín Bán’, and ‘Príosún Chluain Meala’.

The band’s last concert was a 1970 Turlough O’Carolan commemoration in Cork City Hall which didn’t go so well, admits Peadar. “There was a whole lot of things that were mismanaged about it.”

Though band members had joined the Chieftains, Peadar says at the time of his premature death, his father was “planning to amalgamate Ceoltóirí Chualann and Cór Chúil Aodha and take them to Moscow; take them to the Kemper [Quimper] festival, and to the Kentucky Derby”.