Cillian Murphy and the tale of his Cork band who almost made it

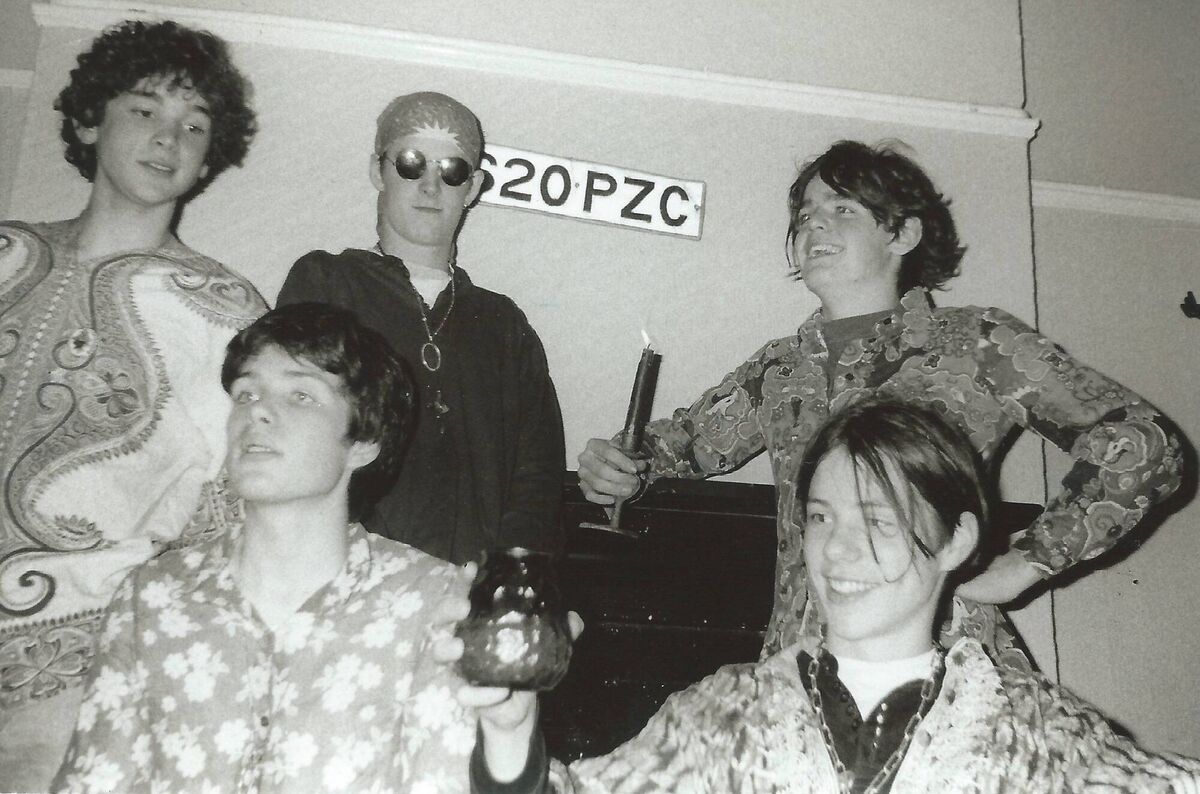

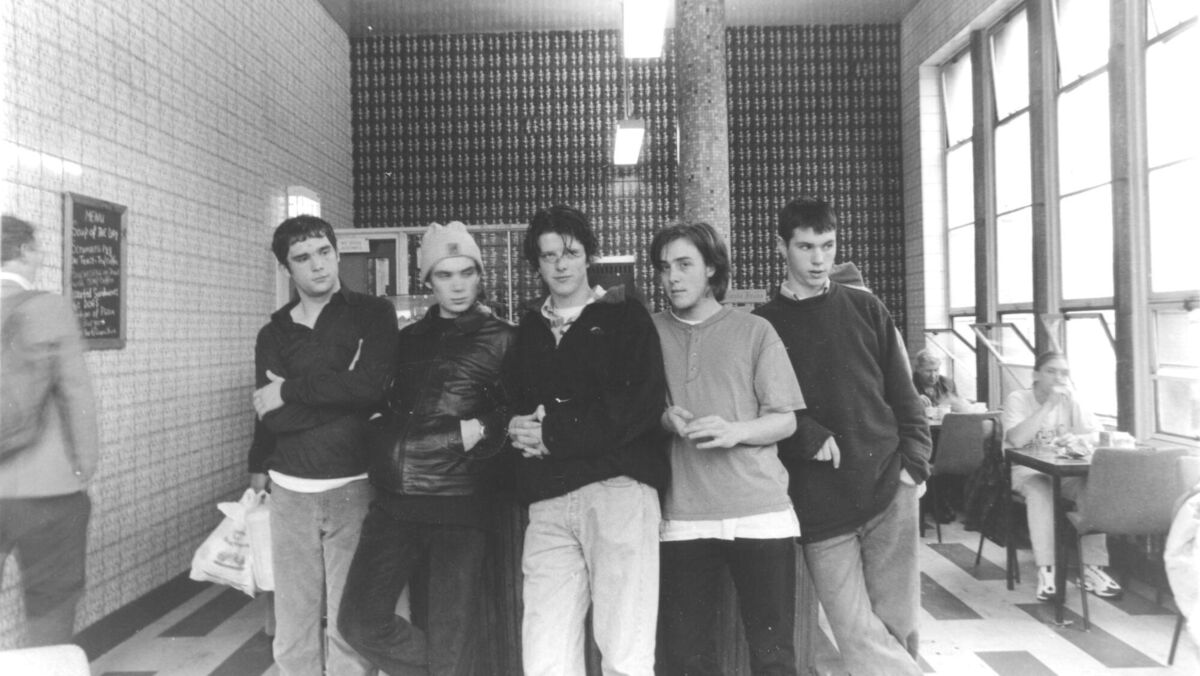

Sons of Mr Green Genes in 1997: Bob Jackson, Cillian Murphy, John Ahern, Chris McCarthy, Padraig Murphy.

Bob Jackson was 12 years of age when he first met Cillian Murphy. It was in September 1989. The pair were starting secondary school in Presentation Brothers College in Cork city. They hit it off immediately, and they’re still good mates 35 years later – Jackson is godfather to Murphy’s son, Malachy; Murphy is godfather to Jackson’s daughter, Nina.

Jackson says a shared, surreal sense of humour has been one of the things they both have in common. “Cillian’s humour often gets lost. It rarely comes across in the serious, troubled characters that he plays,” relates Jackson. “He's the funniest person I know. I’ve had the best laughs of my life with him. We grew up in stitches, messing with each other’s heads, messing with the teachers’ heads, getting up to devilment.

“In school, we got into Monty Python, disappearing down that rabbit hole of Blackadder and other satirical TV shows, absorbing all those absurdist influences, making up our own stories and worlds and characters. It still happens to this day. If we're away for a night catching up, we could spend half the night riffing, playing, say, two cheapskates, arguing about the price of something, acting out imaginary scenarios.”

Besides a love of Pythonesque humour, music also binds the two Cork men. They started a band together in early 1990, with Jackson on drums; Murphy on vocals and rhythm guitar, as well as Murphy’s brother, Pádraig, on keyboards. The first song they rehearsed was U2’s ‘All I Want Is You’. The band went through several line-up variations with, at one stage, Eoin O’Sullivan (guitar) and John Powell (bass) joining and later dropping out, before John Ahern (guitar) and Chris McCarthy (bass) completed their five-man line-up.

The group also cycled through different names, including The Townhouses, and Sarahdaze, before settling on Sons of Mr Green Genes, which was adapted from a Frank Zappa song and hints at their musical direction, which blended funk and indie rock, and ultimately acid jazz, sounding not unlike, say, Jamiroquai.

“Sometimes, we started getting ahead of ourselves with unusual arrangements,” says Jackson. “We’d have a good arrangement with a good beat to it, and then we would throw in these stupidly complex time signatures for no other reason than showing off. We’d have something with a great groove to it, and then we’d overcomplicate it.”

The Sons of Mr Green Genes performed lunchtime concerts at school, practicing in the front room of Murphy’s house in the Cork suburb of Ballintemple to get their 20-minute set down in advance. Their pursuit of excellence didn’t always endear them to Murphy’s neighbours.

“We were practicing, practicing, practicing and a neighbour rang up Cillian’s house anonymously, and was giving out yards,” says Jackson. “The funny thing was, why he was giving out had nothing to do with the volume of the music. It was because we were playing the same song over and over for about three hours. If we could just play a different song.”

The 1990s were a golden period for music and youth culture in Cork city. The Sultans of Ping and the Frank & Walters were two bands who made an impact beyond a thriving local music scene, and Sir Henry’s was one of several venues hosting live bands and top-quality DJs.

The Sons of Mr Green Genes went to great lengths to get their look right, feasting in particular on bargains they could pick up in Riddled With Gorgeous, a clothes shop off Winthrop St run by Lorna Sherlock, and Thelonius Funk, a stall run by Joe Kelly, who would later cross paths with the band as an events promoter.

“We would buy tie-dye, floral dresses almost, with these big furry collars on hippie coats, and glittery pants and all these medallions,” says Jackson. “Then we'd go in and play school concerts, setting off smoke machines and stuff.

“I remember at one early stage, we were doing a gig in a hotel in Mitchelstown. Remarkably, it was our parents who were driving us to these gigs. We might have been 15 years old. So, here we were in this hotel on a Sunday afternoon, playing original music, all dressed up in our hippie clothes. I remember Cillian wriggling and rolling around the carpet. He didn’t seem to be in any way bothered or self-conscious, while these people were trying to eat their carvery lunches.”

The band were going places though. Slowly, they built up a cult following. Their gigs at Connolly’s of Leap, a venue in West Cork, in the mid-1990s, are legendary. Posters advertised what was in store. Fans would jump on board a chartered bus or two at the Grand Parade in Cork city, before setting off on a 90-minute trek west.

“I’ll never forget the energy at those gigs, when it kicked off,” says Jackson. “The atmosphere was incredible, the place was jammed with people. They were our best gigs. There was a power cut at one gig just before Christmas Eve. We were maybe two or three songs from the end of the set. The people running the venue came around with candles so we could finish the gig with an acoustic set. It was snowing outside. It was just magical.”

Joe Kelly – the former clothes stall owner who now runs the Live at St Luke’s venue – was an early advocate of the band. “They gave me a demo when they were all around 14 or 15,” he recalls. “Their playing was excellent for their age, kind of in an acid jazz style.”

In later years, the Sons of Mr Green Genes became the house band at Cabaret DeLuxe on Sundays in the Half Moon venue at the back of Cork Opera House.

“We purchased 1970s tuxedo shirts, baby blue, peach, orange, pea green & sherbet and the five lads wore them,” says Kelly. “They would play before, with and after cabaret acts we had. One night after Massive Attack played the Opera House, Horace Andy even joined them on stage for a 20-minute jam.”

Murphy was a born frontman. “Cillian had a brilliant stage presence,” says Jackson. “He was comfortable talking to the crowd. He was a natural in that context from a very young age. Even looking back at a video of us from about 14 years of age, you can see that he’s leaning into the camera. And he’s a brilliant rhythm guitarist and songwriter.”

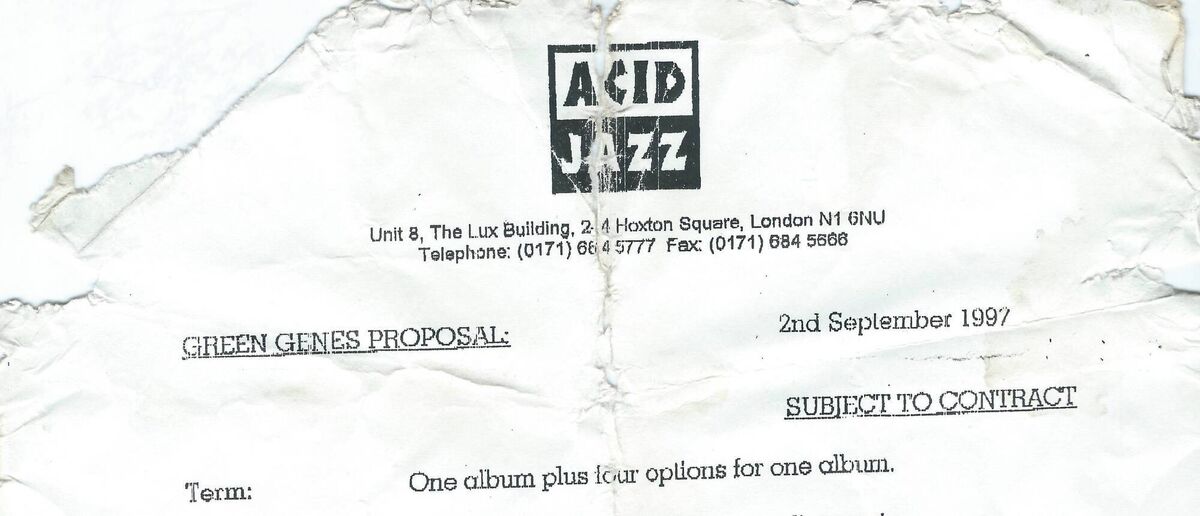

While the buzz grew around the Green Genes, the band hit a crossroads in 1997 when they were offered a five-album contract with Acid Jazz Records, a label founded by Gilles Peterson and Eddie Pillar in London who released records by the likes of Brand New Heavies and Jamiroquai. On paper, the deal was worth £250,000, but this excluded costs and, of course, had to be split between five band members. “It wasn’t a very favourable deal,” says Jackson.

They shopped around for a better offer, talking to other labels like BMG and Warner Music, but nothing came of their search.

By this stage, Murphy’s acting career was taking off, as he had starred in local theatre company Corcadorca’s hit play, Disco Pigs, which premiered in September 1996 and went on to tour internationally for over a year. He made the fateful decision to focus on acting. Sons of Mr Green Genes eventually petered out, playing their last gig in 1997.

Of course, despite moving away from the Green Genes, Murphy has maintained a keen interest in music. As well as presenting an eclectic mix of sounds on his radio show on BBC 6 Music, he has also been hands-on as a co-curator of the biennial Sounds From A Safe Harbour Festival in his home town.

Among the many Leesiders glued to the Oscars in March will be Murphy’s old bandmates. Bob Jackson plans to watch proceedings at home with his wife, complete with a bottle of Champagne on ice. Hopefully, he’ll hear his old friend’s name read out for the Best Actor award, and will get to pop that cork.