Culture That Made Me: Eamon Carr of Horslips on Dylan, Ginsberg, and boxing

Eamon Carr of Horslips fame has a new book about boxing. Picture: Killian Ginnity

Eamon Carr, 74, grew up in Kells, Co Meath. In 1971, he co-founded Horslips, and was the band’s drummer and lyricist. During a varied career, he has worked as a writer, journalist, broadcaster, art historian and independent record label supervisor.

- He is the author of several books, including Showbusiness with Blood: A Golden Age of Irish Boxing, which will be published by the Lilliput Press on Thursday. See: www.lilliputpress.ie.

I was at boarding school in the 1960s. There was a lad who we called “The Professor” because he was a bookworm. He gave me a copy of Lonesome Traveler, a book of travel stories by Jack Kerouac. I hadn't heard of him before. It was a Diocesan college. We weren’t allowed radio or newspapers. So this book had to be shared under the blankets. When I read it, it blew my mind. I still read it from time to time. The prose was explosive, like nothing I’d read before. It changed everything for me because straight away I followed that up by getting my hands on Big Sur, The Dharma Bums, Visions of Gerard, and, of course, it was my introduction to the Beats.

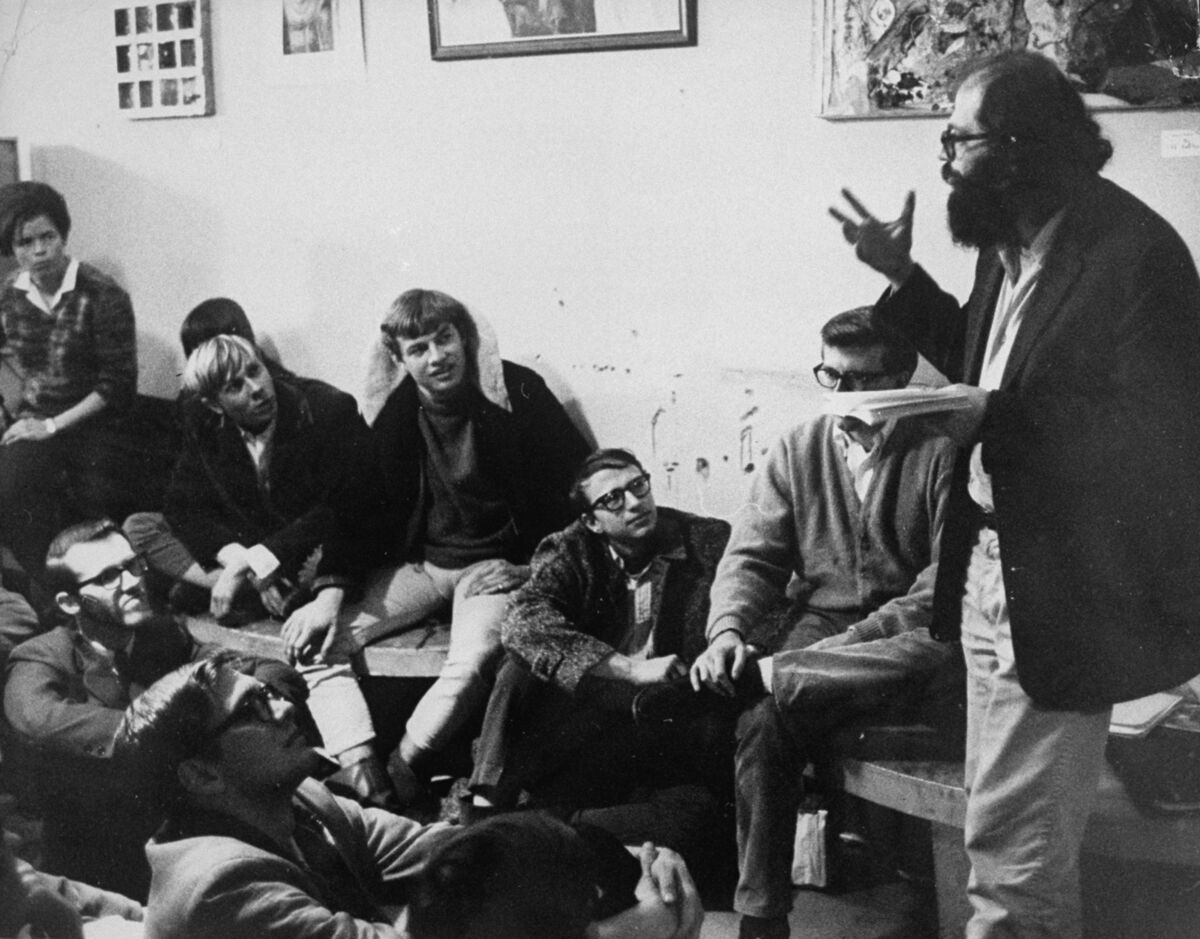

Allen Ginsberg was monolithic. He was astonishing. For me reading him in, say, 1965, studying for my Leaving Cert, and to read a line like: “… listening to the crack of doom and the hydrogen jukebox...” I thought: yeah, now there you go; I know what you're talking about. We had the Cuban Missile Crisis a few years earlier, and “ban the bomb”. He was able to put his finger on the pulse. His work was monumental.

There were lots of minor Beat poets I liked. A guy called Dan Propper wrote a long poem called The Fable for the Final Hour. It was lists, but when you read it, it grabbed you. I only came across bits and pieces from him. I’d find him in compendiums of the Beats. I didn’t know much about him, but he had an energy that I subsequently heard in Bob Dylan. Epic poems. He felt vibrant, contemporary, insightful and on the edge, which made a lot of sense at the time because that’s where you wanted to be!

Around 1967, Penguin published a collection called The Mersey Sound. It was a series of contemporary poets like Roger McGough, Adrian Henri and Brian Patten. They had this incredible ability to communicate. Their voices were fresh. It was described as pop poetry. It was way sharper than pop lyrics, but the sensibility, the core message was digestible. The poems had epiphanies, but were dressed in the form of a pop song or advertising slogans. It was pop art, and they were able to perform live. They were great readers. It was incredibly vibrant. At the time, the likes of Austin Clarke would sit in a chair and intone his poetry and you had to work with it. This grabbed you. It made you want to cheer. It was exciting. Let Me Die a Young Man’s Death, poems like that.

In the late Fifties, it was a very staid life in Ireland. To hear Little Richard was an explosion. It sounded like something genuinely that was being beamed in from outer space. I wouldn't have realised it at the time, but it was New Orleans music. Earl Palmer was on drums. That drum sound was astonishing. It had a kick. Something that you weren't used to because céilí bands didn’t have that rhythm.

A couple of years later, the Beatles arrived. I remember hearing 'Love Me Do', their first single, and I was astonished. There was something haunting about it, a bit of echo on it, with this harmonica. They had this unusual phraseology as well: “Love, love me do”. You didn’t hear that sort of thing. The harmony was very interesting. I became captivated by that, and investigated it. Over the next year, there was this British beat boom explosion. It was exciting. Everything became accessible. It felt like you could tap into this. You could understand it. These people had names you understood like McCartney. It was within reach.

At the same time, in 1963, a programme called Ready Steady Go! on BBC television started broadcasting. It was in black and white with this pop art aesthetic. The co-presenter Cathy McGowan looked like Twiggy with long hair. It had a parade every week of incredible artists: The Zombies, The Animals, The Who. It was pop art. It was five, four, three, two, one. It was fun and outrageous and it was challenging the Establishment, in a slightly gentle fashion when you look back on it, and what was to come later, but that was thrilling. That was my gateway, my entry point into music.

The first time I heard Bob Dylan singing 'Masters of War' or the 'Ballad of Hollis Brown' was astonishing to me. It was easy to relate to him because we grew up with 'Kelly the Boy from Killane' and 'The Minstrel Boy', and the Irish ballad tradition. There was something about the Beats about Dylan, but there was also something about The Clancy Brothers about him. He bridged this gap. When I heard The Byrds singing 'Mr. Tambourine Man', I said, “Oh, my God, there’s something astonishing happening here.”

I came across a Penguin classic called The Narrow Road to the Deep North. It’s a collection of the Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō's travel sketches, which is basically haibun with little haiku interspersed, capturing an account of his travels. In the seventeenth century, he went around Japan with a satchel, as a monk, living hand to mouth, visiting sacred shrines, essentially going into the forest and confronting his demons. I find them really moving, poignant, insightful and uplifting. It probably resonated in a way for an Irish Catholic boy that I was reading somebody saintly on a pilgrimage, on a voyage of inner discovery. It’s wonderful.

You'd be hard pressed to find a more brilliant opening line than the intro to Jonathan Rendall’s This Bloody Mary Is The Last Thing I Own: “It was a few hours after Frank Bruno attacked me at Betty Boop's Bar in the lobby of the MGM Grand that I decided to get out of boxing.” The book is subtitled 'A Journey to the End of Boxing'. It begins in Las Vegas, but it goes back to his school days when he started boxing. He became a journalist who decided he would manage a boxer. It’s beautifully written. An essential read.