Tom Dunne: From Springsteen to my own work, dads in songs can be tricky business

Tom Dunne's father and mother, Tommy and Bridie, with family members at their wedding in 1947.

Dads get a rough ride in music. They are largely utterly absent (Exhibit A: Harry Chapin's The Cats in the Cradle –“We’ll get together then son”) or smug, all knowing, pr**ks (Exhibit B: Father and Son, by Cat Stevens – “For you will still be here tomorrow, but your dreams may not”). There is little middle ground.

And those songs were from a gentler time in music! More contemporary songwriters have tended to be less ambivalent. Martha Wainwright’s paeon to her dad is called Bloody Mother F***ing Asshole. This, on examination, turns out to be a perfect, possibly understated, response to the parenting skills of one Loudon Wainwright III.

He had long performed a song called I’d Rather Be Lonely, which she had always assumed was about some adult relationship. But then, one night at one of his gigs, she heard him introduce it by saying, “I wrote this song about my daughter.”

It turned out to be about the year they had lived together in New York when she was just 14. That year had been, by all accounts, a disaster and the song was about it. Fans of the Wainwright family will know that this excoriating honesty in song is almost a family tradition. But still, go easy lads.

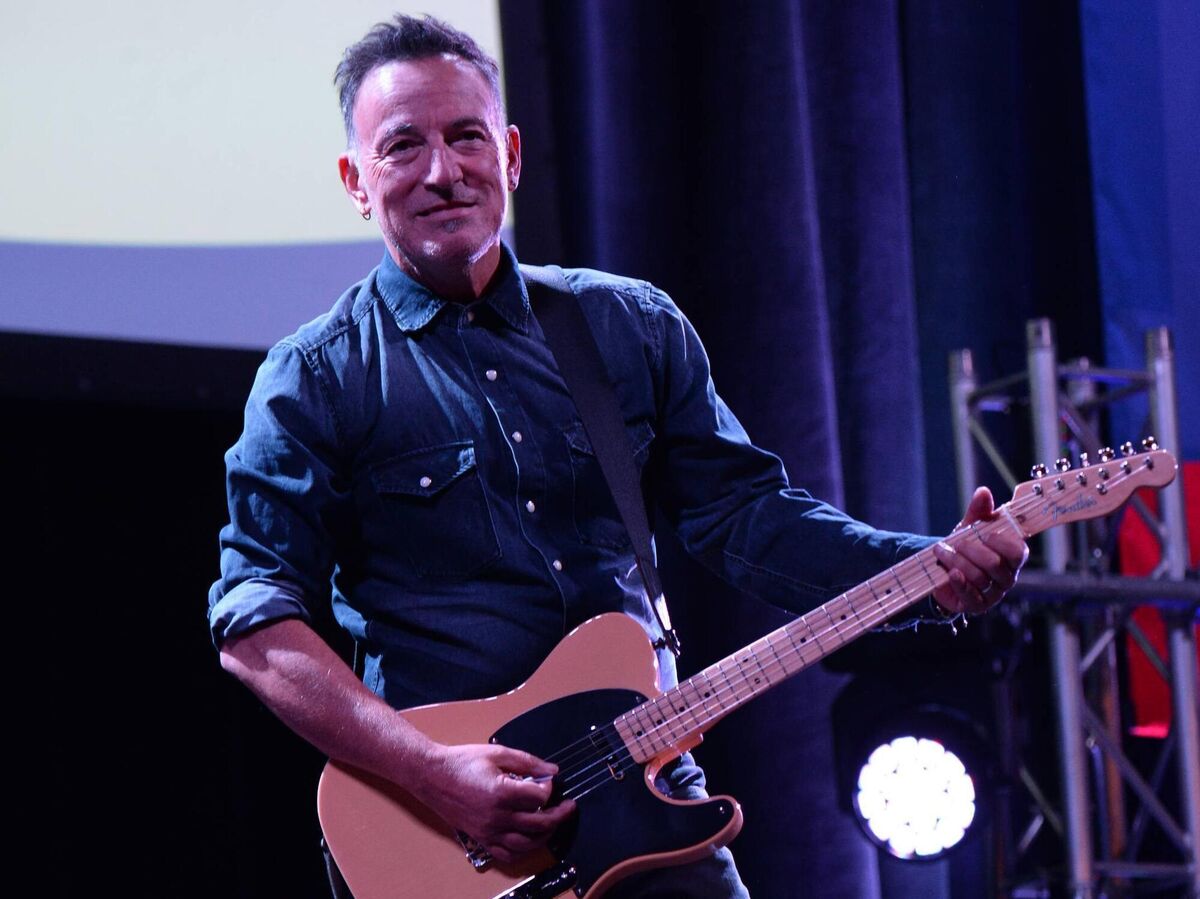

For a more rounded look at issues in the Father/Son world the man you need is Springsteen, “My entire body of work, everything that I’ve cared about, everything that I’ve written about, draws from his life story." Douglas, his dad, informs his stage show, and his songs, like a constant ghostly presence.

Bruce says he was in “hardcore analysis” by the time he was 32, hence his examination of that relationship is nuanced and deep. He has written about it in songs like My Father’s House but the killer address remains in the live introduction to The River at performances during the '70s.

Here he would talk about early clashes with his dad. It seems cliched enough, his dad wanting him to cut his hair and get a job and quipping, when Bruce reveals that he has been called up for the Draft to Vietnam, that at least the army will make a man of him.

But the truth of their relationship emerges when Bruce tells him he has failed the medical. You are waiting for a ‘can’t even do that right’ remark from his dad, but as the older man looks into his eyes, realising his only son will not be going to Vietnam, all he can say is, “Good.” It’s powerful stuff.

So where is my dad in anything I’ve ever written? The answer would be absent, not there, standing out by reason of his non-inclusion. But why? He died when I was 29, it’s not as if I didn’t have time to get to know him.

I remember patchy things about him: A Man Utd strip he got me when I was seven, a bottle of Old Spice aftershave he got me when I was nine, him singing songs by Count John McCormack. These songs always built to a crescendo. He would hold the mantelpiece to steady himself for the high note.

But we never really spoke. He never shared a moment of his past life – working in England in WW2, for instance- with any of us. But he would read the comics to me every Saturday in bed when I was tiny, and I was probably there ready to go at first light, and find pocket money for me somehow throughout my time in UCD.

When I was studying for exams he used to call up to me to ask if I wanted tea. Being a rude teenager I would treat this as an incredible intrusion and refuse point-blank. But he would also make sausages and eventually the aroma would draw me down.

“There’s tea in the pot,” he would say gently, hardly looking up. There would also be a sausage sandwich on the table. “Is that spare?” I would reluctantly ask. “Yeah, I did an extra one.” I would then finally sit opposite him and eat.

We’d sit in silence, him reading his paper, me truly loving the sandwich. If I could go back now, obviously, first things first, I’d punch teenage Tom. And then maybe I might ask: “So how come you can play piano? And why does a man from Inchicore follow Wolves? And, maybe, who are you, Da?”

For now, though, Billy Bragg’s classic father-son song, Tank Park Salute, will have to do.