Cork in 50 Artworks, No 19: Controversy and rancour at The Great Wall of Kinsale, by Eilis O’Connell

Eilis O’Connell. Picture Clare Keogh

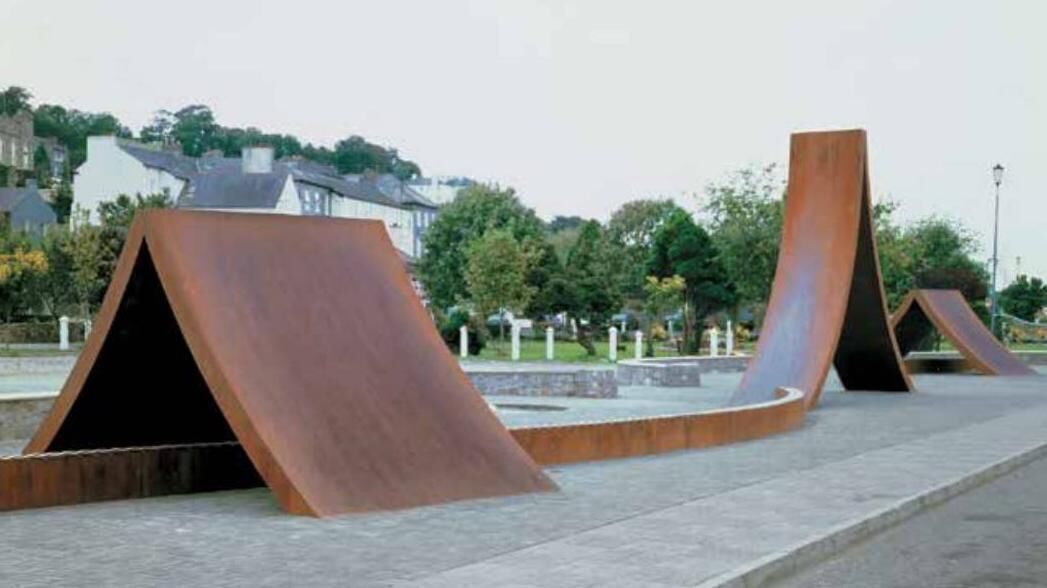

[first published August 2021] Eilis O’Connell’s The Great Wall of Kinsale is one of the most contentious public artworks ever erected in Ireland. Commissioned by the Arts Council, to mark Kinsale’s success in the Tidy Towns competition in 1986, it was assigned a prime site between the Town Park and the pier road. The £36,000 budget was one of the largest for a public artwork at that time.

O’Connell had already won considerable acclaim when she was awarded the commission. A graduate of the Crawford College of Art, she had gone on to study sculpture at the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston. In 1981, aged 30, she won a GPA Award for Emerging Artists, and three years later she was elected to Aosdána.

O’Connell’s proposal was for a series of undulating forms in corten steel, a material whose rusted appearance and texture would change subtly over time.

“I had trained under John Burke at the Crawford,” she says. “I could weld, and I knew metal, I knew what could be done with it.” O’Connell remembers making a number of presentations on her proposal, and believes that one of these was a public presentation at the Town Hall in Kinsale.

“I had made a maquette of the work, so people would know what they were getting. There were no objections.”

Dermot Ryan of Kinsale Heritage Town Walks was Chairman of the Tidy Towns committee at the time, but he doesn't recall any public presentation.

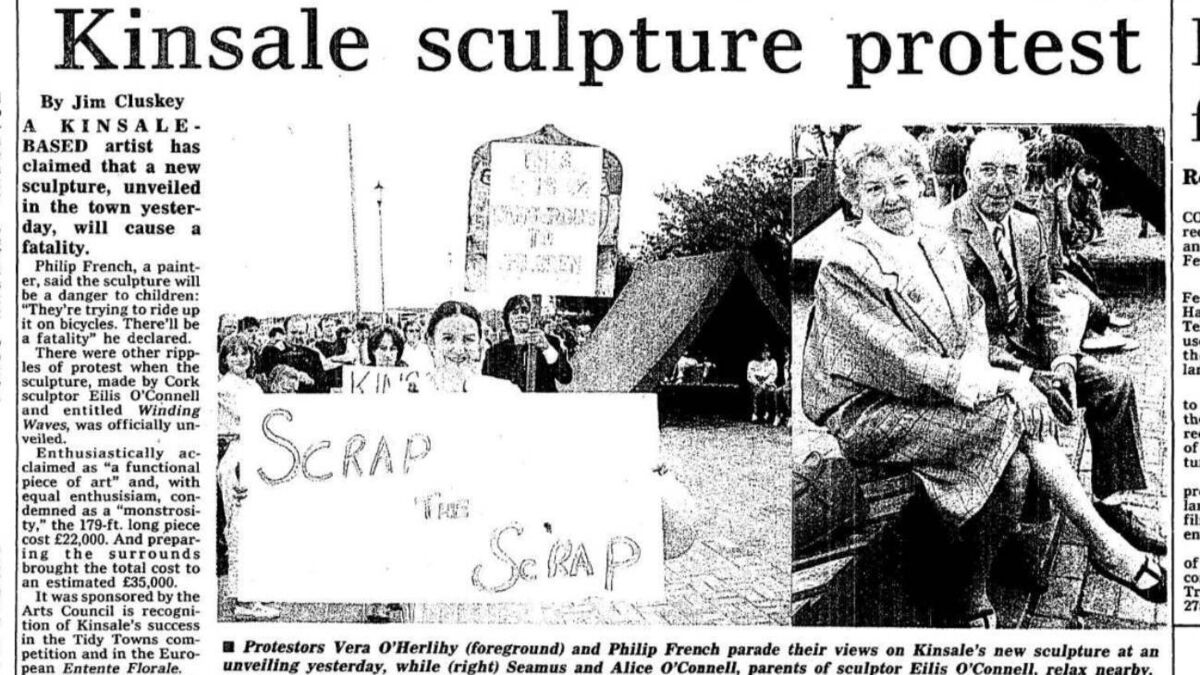

Whatever the circumstances, there was no inkling of what was to come. Indeed, once Kinsale UDC approved O’Connell’s proposal, by a vote of 7:2, the whole project seems to have proceeded smoothly; the installation of The Great Wall of Kinsale went ahead as planned, and the late Joe Walsh TD was called on to unveil it, at the Regatta on July 24 1988.

On that occasion, Walsh described The Great Wall of Kinsale as “a most idyllic and beautiful piece of work.” He said it would rival any he had seen in the major European cities, such as Edvard Eriksen’s The Little Mermaid in Copenhagen, and he was happy to learn that it had already become a location for romantic trysts.

“I hope that in years to come the conviction of those who support it will be vindicated,” he concluded, sounding a cautionary note that perhaps spoke to his astuteness as a politician.

For not everyone shared his enthusiasm. “It was very controversial,” says Ryan. “People were delighted when we won the Tidy Towns, but there were mixed feelings about the sculpture. There were people with placards protesting on the day.”

O’Connell had to miss the launch, as she was on a fellowship in New York. She was shocked at the negative reaction when next she visited Kinsale. “I was verbally abused, and had stones thrown at me,” she recalls.

Initially, the objections seemed to be over safety; there were fears that youngsters would be tempted to climb the wave forms, or scramble up them on their bicycles or skateboards. “The danger was that they would fall off, and go out onto the road,” says Ryan.

But the rusted appearance of the work also drew considerable criticism. “The artist used corten steel, which was supposed to turn a blue-ish colour in time. But it was the wrong material for a place like Kinsale, it didn’t look good.”

This objection at least could be attributed to the public’s unfamiliarity with the material; today, corten steel is more visible, used as it is in the Wild Atlantic Way signage up and down the west coast.

A proposal to remove The Great Wall of Kinsale was defeated by Kinsale UDC in April 1989, but support wavered soon enough. Adjustments were made to the work without O’Connell’s consent: the corten steel was painted over, railings were installed, and holes were cut at the top of the forms so they could be converted to water features. O’Connell found that offensive enough, but often the water was not even turned on.

“At one stage,” she says, “there were five stagnant pools at the base of the structures.”

The waterfalls and pools were later removed, but O’Connell was so upset by the interference in her work that she left the country, accepting a residency at the Delfina Studios in London, and she stayed in the UK until 2002.

“Ironically, all the big commissions I got over there were on the strength of my work in Kinsale.”

These include large-scale public sculptures such as Ever Changing in Newcastle; Unfurl at Kensington Gate in London; and Pero Bridge in Bristol.

O’Connell still feels public artworks are not properly cared for in Ireland. “In the UK, for instance, my work at Newcastle is cleaned every two weeks. My contracts stipulate that my artworks are to be maintained. But here in Ireland, we don’t seem to want to maintain our public sculptures at all.”

Today, The Great Wall of Kinsale bears little resemblance to the artwork O’Connell installed in 1988. She never goes back to Kinsale, and hasn’t checked in on it in years. “For me, the piece has been destroyed. I couldn’t bear to see it now.”

Joe Walsh TD thought The Great Wall of Kinsale the equal of Copenhagen’s Little Mermaid, but tellingly, it does not feature on the tourism portal, Kinsale.ie.

Ryan says the sculpture still inspires “mixed feelings” in the town, but “people have got so used to it now, they ignore it. You can shelter under it if there’s a shower of rain; you’d be surprised at how much space there is under the middle form. And the seats are handy if you’re waiting for the bus.”