Cork In 50 Artworks, No 16: Statue of St Gobnait at Ballyvourney, by Séamus Murphy

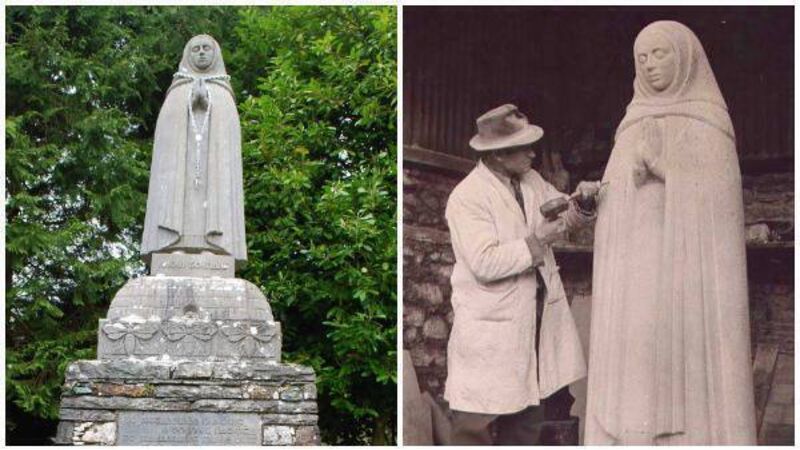

Statue of St Gobnait at Ballyvourney, by Séamus Murphy; right, Murphy at work on the statue.

Séamus Murphy’s limestone statue of St Gobnait at Ballyvourney features a life-size representation of the saint.

She is dressed in a shawl and perched on a beehive, around which are relief figures of the bees with which she is often associated; it is said she used honey in curing the sick, and directed her bees to terrorise anyone who threatened her community.

Murphy’s statue was commissioned by a local committee, chaired by the parish priest Fr Tom O’Brien, and unveiled on 13th May – Whit Sunday - 1951.

Murphy’s son Colm recalls that it was one of the late Cork artist’s favourites of all his sculptures, and it is not hard to see why; its simplicity and beauty recall that of the work of Marcel Gimond, with whom he had studied in Paris in the early 1930s, but his use of apian motifs attests also to his love of local history and legend.

Indeed, were it not for the figure’s hands being clasped in prayer, Gobnait could easily be mistaken for a pagan deity, which is perhaps why someone in recent times has hung a chunky set of rosary beads around her neck, as if to confirm that she is in fact a Christian figure.

Gobnait is said to have been born in Co Clare in the 6th century AD. One night, an angel appeared to her in a vision, advising that she would settle in the place where she came upon nine white deer.

Thereafter, she wandered through Cork and Kerry, finally encountering the nine white deer of her vision by the banks of the Sullane river at Ballyvourney, where she founded a convent and is buried.

“Everyone in Ballyvourney thinks of Gobnait as one of our own,” says Hannie Corkery, whose paternal uncle, Fr Denis Corkery, delivered the sermon at the statue’s unveiling.

On that occasion, Fr Corkery remarked on how “some clever people said it was useless to rely on the saints for release from their physical troubles. But clever though these people were, they were wrong.”

As it happened, Hannie Corkery’s maternal uncle, Dan Lucey, was one of those believed locally to have been cured of an illness through St Gobnait’s intercession.

“When Dan was five or six,” she says, “he had a bone condition, and he was not expected to live. My grandmother carried him to the shrine, and then to the church, where she asked the priest to say the Mass for him. When Mass was over, the priest came down to her, saying Dan would be cured. He was, and he lived to 96.”

That Murphy was asked to commemorate St Gobnait is testimony to the bravery of the local community and its clergy, according to his son. By 1951, Murphy had fallen out with the powers-that-be in the Catholic Church, and he was passed over for many important commissions in the next few decades.

“The problem was,” Colm explains, “my father did a bust of John Charles McQuaid [the powerful Catholic Primate of Ireland] in the early 1940s, but McQuaid didn’t like it at all. He rejected the bust, and told the Bishop of Cork, Con Lucey, not to commission any more work from my father. And believe me, we went hungry as a consequence.”

Thereafter, any priest in Co Cork who commissioned work from Murphy did so on his own initiative. “They would have been flying in the face of the bishop’s instructions. And I’m sure they suffered for it.”

Murphy carved his statue of St Gobnait at his workshop in Blackpool in Cork city, but he would first have designed it in the upstairs room at his home in Wellesley Terrace that his son, himself a painter, now uses as his studio.

Today, there are any number of Murphy’s busts and drawings around the room, and the wooden drawing board on which he drew out his designs leans against a chair.

“Those bees at the base of the statue, for instance, he would have designed at the table over here, and he would then have traced them onto the stone at the workshop in Blackpool.”

Murphy’s statue of St Gobnait is not the only example of his work at Ballyvourney. Among the headstones in the graveyard nearby are those he carved for the poet Seán Ó Riordán and the composer Seán Ó Riada.

Carving headstones was Murphy’s bread and butter – he even carved his own – and it was work he took great pride in. “My father was a stone carver first and a sculptor second,” says Colm Murphy. “And not the other way around.”

Twice a year, on St Gobnait’s feast day on February 11, and again on Whit Sunday, devotees complete a “pattern” in her memory, praying at Murphy’s statue; at what is said to be Gobnait’s house nearby; at her well; and at her grave.

But locals such as Hannie Corkery visit regularly, and the site is beautifully maintained.

“There’s a group of us, all women, who come here every Sunday morning,” she says. “Séamus Murphy’s statue may only have been with us for seventy years, but it’s a much-loved and valued part of St Gobnait’s round.”