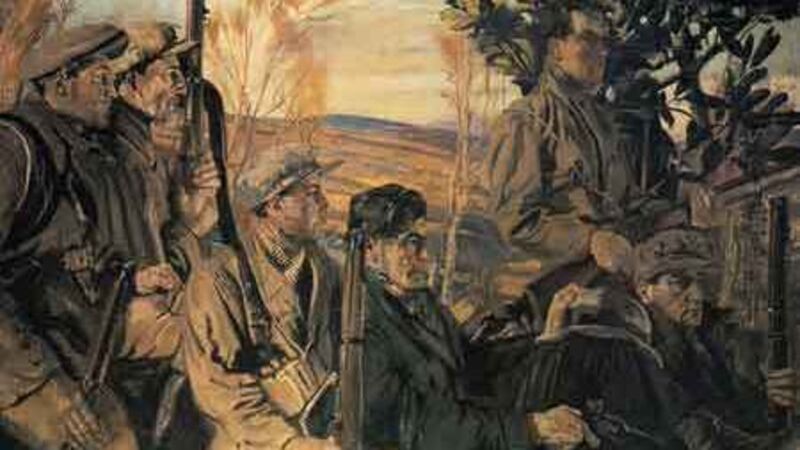

Cork in 50 Artworks, No 14: Men of the South by Seán Keating

Men of the South depicts a scene during the turbulent creation of a nascent state. Picture: Crawford Art Gallery

Bought by the Crawford Art Gallery in 1924 for £200, Men of the South has become one of Cork’s most-loved works of art, priceless in terms of the enjoyment it brings to the citizens of the city where it resides. Seán Keating’s oil-on-canvas painting of the members of the North Cork Brigade during the War of Independence is deservedly described as iconic.

The fact that descendants of the men who feature in the painting — Jim Riordan, Denis O’Mullane, Jim Cashman, John Jones, Roger Kiely, and Dan Browne — still live in Cork also preserves a link with the work, according to art historian Eimear O’Connor, author of the biography, Seán Keating: Art, Politics and Building the Nation.

“That painting is Cork and is of Cork — if anything happened to it, the people of Cork would be up in arms. Relatives of the sitters still live in Cork, I have met them. Cork is very proud of it, and it is right to be, it is an iconic piece of work,” she says.

Keating, a Limerick native, invited the brigade commander, Seán Moylan, and his men to sit for the painting in the summer of 1921, during a ceasefire in the War of Independence. Moylan, however, while present at the sitting, did not appear in the final painting, as he was afraid he would be too easily identified.

“It was done from photographs, and one can see from those that they are young men — Keating makes them look older in the painting so they can’t really be identified,” says O’Connor.

“Moylan is, however, in 1921: An IRA Column, another painting by Keating. It is hanging in Áras an Uachtaráin, the President loves that painting.” (A second, unfinished version of Keating’s painting, with Moylan included, also hangs in Áras an Uachtaráin.)

According to O’Connor, Keating knew he was living through a significant moment in Ireland’s history and was painting with posterity in mind.

“Keating always wanted to paint emerging history. He wanted to be there on the spot. That is also why he documented the Shannon Scheme. He knew what he was doing, that it was going to be an iconic painting for the future. It is important to get across the historical significance of the work and what Keating is trying to do — to appeal to people living now, going in to look at that painting. He wants everyone to feel the tension of the time.”

Described by artist George Atkinson at the time of its purchase by the Crawford Art Gallery, as a “good painting, possibly even a great one”, O’Connor is in no doubt about the painting’s artistic merits.

“That was very good coming from George Atkinson, because he couldn’t stand Keating, he was his headmaster in the Metropolitan School of Art,” says O’Connor.

“There is nothing that I don’t like about the painting. I like the composition of it, it is a very clever composition. I like the fact that we are observing the men observing something else. They are all on watch, they are slightly tense. He is trying to disguise the sitters in a way, yet tell you who they are and what they are feeling. It is very masculine yet it is a gentle view of them. He brings the viewer right into the painting as part of the group. I love the colour, the landscape. It is a wonderful portrait of men who are fighting for their country, that is their ideal, but it was the ideal of a lot of people. I love his skill in telling us that story now, through this painting of just a few men.”

Keating kept painting until he died in 1977, aged 88.

“He loved the painting, he knew it was one of his best works,” says O’Connor. “He was very proud it was bought through the Gibson Bequest that brought it into the Crawford.” One hundred years after its creation, Men of the South gives us an insight into the turbulent creation of a nascent state and a reality that is hard to comprehend now.

“Keating lived through the times that made Ireland now. I don’t think we can even get our heads around what it must have been like then. They were walking around during the War of Independence, the Civil War, with bullets flying past their heads. I had access to Keating’s diaries where he writes about waking up with screaming nightmares, he never really tells you what happens but very few people did because they were traumatic, awful times,” says O’Connor.

According to O’Connor, Keating would have taken great satisfaction in the pleasure that his painting still brings to visitors to the Crawford and the special place it holds in people’s hearts.

“The Crawford, like all municipal galleries, is very important and greatly valued by local people, and it is part of the pattern of their daily lives. Keating would have loved that, that was what his art was for. He believed all galleries should be free, accessible to all and everyone should be educated in the visual arts.”