Cork In 50 Artworks, No 5: Cork poets mural, by Tom Doig

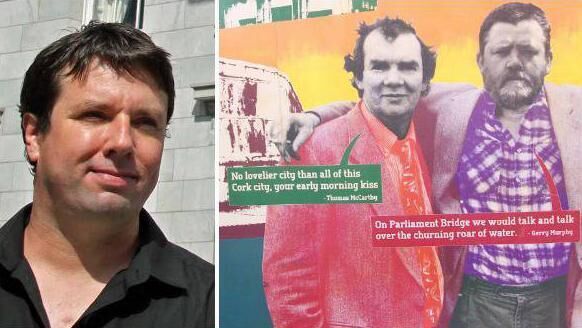

Tom Doig's mural on North Main Street in Cork.

Of all the Cork artworks in this series, most are meant to stand the test of time: some are monuments, hundreds of years old, while others are housed in galleries and similar institutions.

But Tom Doig’s Cork poets mural was far more ephemeral than that. All the artist has left to remind him of the piece that remains his own favourite outdoor mural is a scale plan of the paint and collage piece.

“It’s 1 millimetre to one centimetre, I think, and it’s in a right state because it’s gotten wet a few times,” Doig says, unfurling his plan for the video-call screen.

The mural graced a hoarding at a derelict site on North Main Street for a mere matter of years: it was created in February 2014, to celebrate Cork Spring Poetry Festival. And it was removed at an unknown date in recent times. Even Doig himself doesn’t know when it was dismantled.

“Towards the end, it was getting really shabby and, I was kind of avoiding it and then one day I looked down the street, and there was a new hoarding there,” he says. “But you have to expect that, with artworks that are outside.”

So all that remains of the mural, which captured not only an aggregated Cork cityscape centred around its historic quaysides, but many rebel city wordsmiths, is Doig’s scale plan, and the fact that the mural is captured, in a semi-decrepit state, on Google Street.

Paradoxically, during the mural’s short reign over the city’s historic main street, it felt like a permanent fixture, capturing not only the city, but the familiar faces of the city’s poets. And Cork, Doig freely admits, was for a long time a city of writers more than a city of visual artists.

“Yes, Cork has always been about music and literature,” he says. “But I think it’s tipped the other way now, and there’s more visual art out there, and visible on the streets.”

Doig, a Crawford College of Art and Design (CCAD) graduate, has contributed to this visibility in no small way with his public artworks, including 2016’s Flags of the Townland, which saw an iconic Shandon building clad in imagery from old butter wrappers, and an Ocean to City mural celebrating Cork’s currachers on St Patrick’s Quay.

The Cork poets mural was a commission, Doig explains: Pat Cotter, the director of the Munster Literature Centre, worked with Doig, identifying the artists and passages of their poetry for inclusion in the artwork.

Gerry Murphy, Martina Evans, Louis de Paor, Theo Dorgan, Liz O’Donoghue and others are depicted, with an excerpt of their own musings on Cork city, against the backdrop of Doig’s composite city.

Disaster struck early in the installation of the artwork. 2014 was the spring that Storm Darwin hit Ireland. Doig, who had already prepped and primed the hoardings he was to work on for the mural, found himself without a canvas: the hoardings blew away in the storm.

“We had to get more funding and actually replace the hoarding ourselves,” he says with a grin.

With the help of first year CCAD students, Doig reprimed his fresh canvas and started anew. Working from his scale plan, the background was gridded out and painted. Then collage elements were pasted into place with PVA glue: photos Doig had taken himself of buildings, alongside portraits of poets from West Cork photographer John Minihan’s book, An Unweaving of Rainbows.

“That was then scaled up and printed out, on about two hundred A3 sheets, and cut out by hand,” Doig recalls. A layer of wood varnish gave the completed mural a slightly yellow hue, but offered some protection against weathering.

“I quite liked how it looked after a while, because it started looking quite collagey and worn,” Doig says. “But when we did it, we thought, something would be built there soon, and it would be taken down.” But years on, the site is still derelict, one of many vacant lots in the city that have slowly crumbled. In the ongoing discussion around housing, dereliction is now coming to be viewed as a societal disease in need of a cure. Does Doig worry that his work, in beautifying such dereliction, was a form of gentrification, a way of making it acceptable?

“At the same time, I kind of like the idea that you could have an artwork in the middle of all that rubble and chaos,” he says. “I mean, God; while I was working there, there were all these needles in the alleyway next to it.”

True to this grittiness, the Cork that Doig captured was not the Cork of mythology, of grandiose aspirations, of the status quo, but a city as imperfect, iconoclastic and unapologetically unique as the characters that were its subjects.