Cork In 50 Artworks: The inside story of how Roy Keane was photographed with a rotting raven's head

Mary McCarthy, director Crawford Art Gallery, viewing Murdo Macleod’s portrait of Roy Keane at the gallery in 2019. Picture: Michael Mac Sweeney/Provision

It was late August 2002. Roy Keane’s name was everywhere, not only in the pubs and on the streets of his home city, but in the world of football, which was immersed in two divisive controversies involving Cork’s erstwhile golden child.

In May, the notorious Saipan incident saw Keane walk away from his position as captain of the Irish World Cup team. Then there was the publication of an autobiography of uncompromising, almost reckless candour, amongst whose revelations was the deliberate nature of Keane’s vicious tackle against Man City player Alex Haaland.

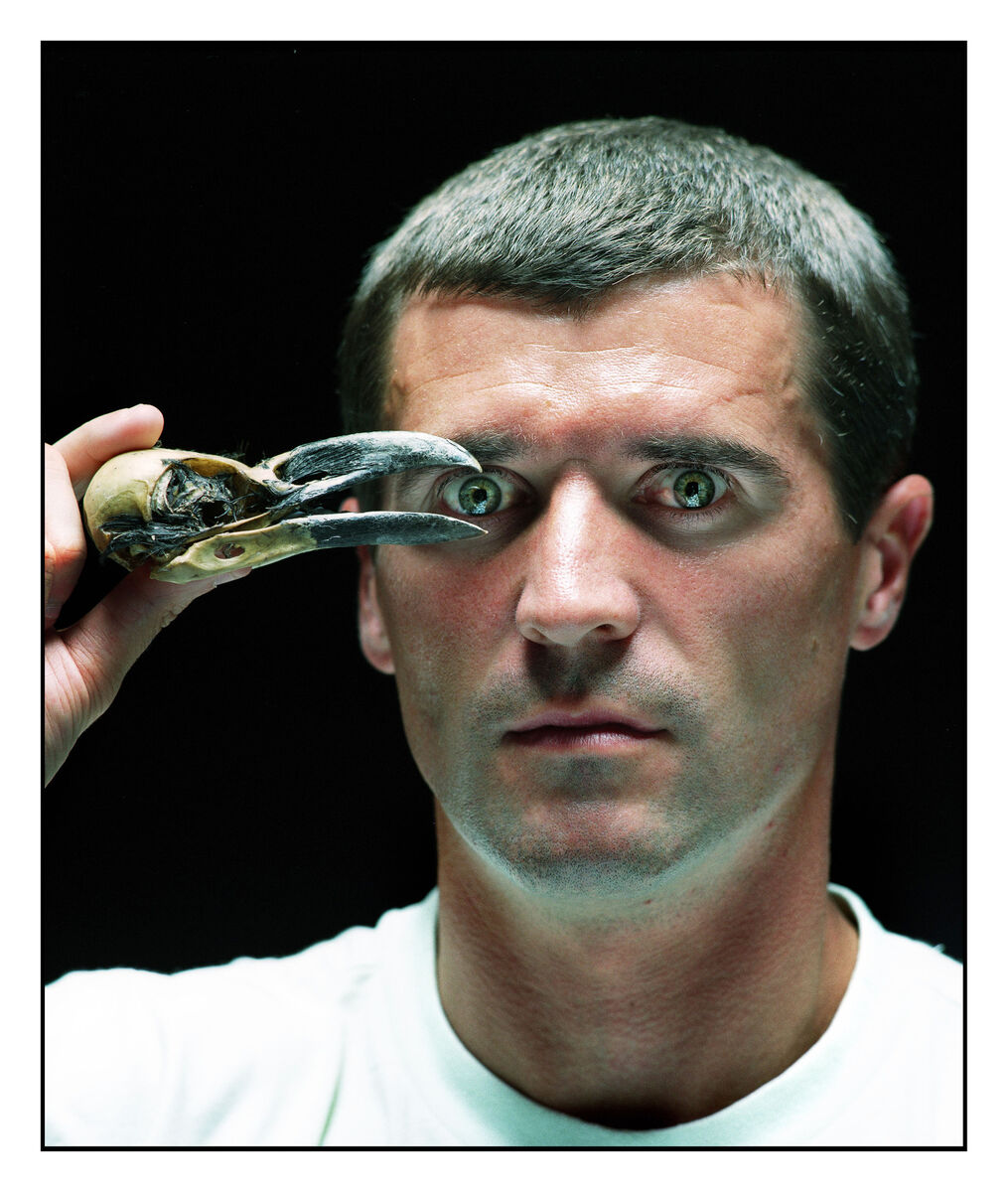

Against the backdrop of all this controversy, Scottish photographer Murdo Macleod captured an iconic image of Keane that hangs in Cork’s Crawford Art Gallery to this day.

Macleod’s use of a prop – a raven skull found on one of his frequent hikes on his native Lewis in the Outer Hebrides – and the time constraints he found himself working under, gave rise to one of those decisive moments that only photography can achieve.

The result is a portrait that reflects Keane’s polarities in the eye of the beholder: a proud, uncompromising warrior, driven to tell the truth and stand up for what he believes in? Or a frighteningly arrogant perfectionist, given to bouts of savagery on the pitch? Both are here. Either way, there’s a magnetic intensity to the image that firmly places it in the pantheon of Cork-defining artworks.

Macleod recalls pacing the hall of Manchester’s Marriott Four Seasons hotel, “seriously agitated”, in advance of taking the photograph.

In a corner of the lounge, Keane was “pouring out exclusive confessions” to journalist and fellow Irishman Seán O’Hagan, who was writing a feature interview with Keane for The Observer. While Macleod knew the content of that interview was dynamite, he was also aware that the interview had run seriously over time, and that he probably only had minutes to do his own job and capture a fitting image of the footballer.

“I am eavesdropping,” Macleod says. “The interview is liquid gold for my colleague. Timewise, I’m in trouble. But I can’t interrupt this thunderous unburdening.

"Finally, Keane walks out towards me, now strangely calm, telling me we only have a few minutes. I abandon all my intentions but one. There is no time for conversation. I produce a polythene bag from my back pocket, and remove the rotting head of a dead raven.”

According to Macleod the skeletal avian prop made Keane wince: it was still smelly, found just a week earlier. He hadn’t kept it specifically with Keane in mind, he says.

“I do a fair bit of walking and have stumbled on a fair number of bird skulls. My favourite one is a heron. I don t really reason, I just look at what is around me. Then I do what I can. This was what I could do.”

Macleod demonstrated to Keane what he wanted him to do: to hold up the skull so that the cruel curve of the Raven’s beak framed his pupil. “’Like this?’ he says. The shutter falls, and almost instantly, time expires.

Magnum photo agency founder Henri Cartier Bresson once famously said: “Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organisation of forms which give that event its proper expression."

Macleod’s description of time expiring is very much in this spirit.

After the timeless moment, things unravelled quickly, with Keane quietly saying, “That’s my taxi now,” before handing Macleod back the raven skull and departing.

After the publication of the article that Macleod’s image accompanied, Keane would face fresh controversies when a serialisation of his autobiography, drove public awareness of his candid admission of a brutal and deliberate foul and led to legal threats from Haaland.

Retrospectively, Keane’s World Cup walkout, in which he highlighted that FAI officials flew first class while players flew second, that Saipan seemed organised more as a junket than a serious preparation for competition, may feel vindicated. As may Corkonians who defended Keane at the time, preferring to see him as misunderstood than traitorous.

However Keane feels about these public controversies today, his home town is left with a fitting portrait, one that captured a decisive moment in the life of what remains one of the Rebel city’s greatest sporting legends.

- This article was first published on April 29, 2021.