B-Side the Leeside: Finbarr Dwyer - Irish Traditional Accordionist

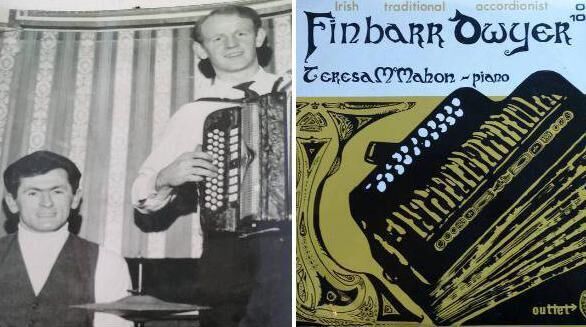

Finbarr Dwyer playing in Slough. Picture Frank Conroy

“Nobody has ever played the accordion like Finbarr and to be honest I don’t think anybody will.” Though many have attempted the feat, few would dispute the assertion of Teresa McMahon, accompanist and long-time friend of the late Finbarr Dwyer.

“He was totally unique,” agrees Kerry accordion maestro Séamus Begley. “He danced reels around the tune and he just could not play it straight. He had to put his own twist on. As he said himself, he gave it the kiss of life.”

Begley speaks from experience, having once offered the Beara man the most sincere form of musical flattery. “I learned a hornpipe that he was playing. I did my best to imitate him and I played it for him. He picked up the box and played a different version,” laughs Begley, who in 2010 presented TG4’s Gradam Ceoil composers’ award jointly to Finbarr and his brother John.

Teresa McMahon, piano accompanist on Dwyer’s early albums, attests that he rarely played a tune the same way twice, just one of the idiosyncrasies of a mercurial musician and composer who played both fiddle and guitar left-handed, without modifications to the instruments.

His multi-instrumental skills and breadth of Irish, continental, and country and western styles found receptive audiences in the pubs and clubs of Cricklewood and Shepherd’s Bush, in Camden, Kilburn, and Slough of the late 1960s and 70s.

“The Irish were there in their droves and every night we went out to play it was full of laughter and song and fun,” says Teresa, who with her husband, Clare accordionist Martin McMahon, became fixtures on the London Irish music scene as The Caravelles, playing regularly with Dwyer.

“Himself and Martin became great friends and he was always visiting us, and he would turn up at some of the places we would play. He played so many instruments and composed a lot of music; he played the most beautiful continental waltzes.”

‘Finbarr Dwyer, Irish Traditional Accordionist’, comprising Dwyer’s own compositions and his distinctive twists on traditional tunes, was produced by Billy McBurney at International Studios in Belfast and released on Outlet Records in 1970.

Its recording was a no-nonsense affair, Teresa recalls. “I was in England and I flew over in the morning and back in the evening. I met Finbarr in the studios. The recording was all done in one day - you sat down and you did it.” Launched with similar lack of fanfare, the album nonetheless “made a massive impact” says Teresa. “Everybody wanted to hear him.”

Playing to packed houses at the likes of the Galtymore, the Seven Stars in Shepherd’s Bush, and the Crown in Cricklewood, the year of the album’s release also saw Dwyer perform in the opulent surroundings of the Royal Albert Hall for a St Patrick’s Festival concert.

Since his move to London in 1966, Dwyer had taught part-time in Bishop Ward Roman Catholic Secondary Modern School in Becontree Heath, near Dagenham, despite having left Dublin before completing his teacher training. For Dwyer, who went on to found a successful transport business serving construction sites, music was both pastime and paid employment.

His playing partnerships in the English capital included one with his cousin Seán O’Dwyer of Ardgroom, who arrived in London as a college student in 1968.

“We had three gigs at the weekend, at the Camden Stores on a Friday, on Saturday night in the Irish Centre in Camden Town, and on Sunday nights we used to play in the Falkland Arms, which was up in Kentish Town,” says Seán. “It was owned by a Kerryman, Gene McCarthy, who came from the nearest parish [to Ardgroom] in Kerry, a place called Lauragh.”

Beara connections were strong in London, Finbarr’s homeplace in Cailroe being just four miles on the Cork side of the peninsula’s county bounds, in a remote pocket of traditional music. Finbarr’s mother Kathleen was an accordion player, singer, and lilter. His father John played accordion and fiddle and was influenced by the musicians, including Waterford piper Liam Walsh, whom he had met while imprisoned on Spike Island during the War of Independence.

The couple’s children inherited their parents’ musical gifts, notably Finbarr’s brothers Richard, Robert, the late whistle-player Michael, and fiddle-player John, who passed away last year.

“All the Dwyers of Cailroe were gifted, and composers as well,” says Seán. “Finbarr’s father, my uncle John, was brilliant, a great step dancer and a sean-nós singer, a Munster champion at both.”

Seán relates how he and Finbarr also tried their hand at competitions, winning the concertina and accordion titles respectively at the 1969 All-Britain Fleadh in Glasgow, also carrying off all the prizes at lilting, or “gob music, we used to call it, that we heard our parents doing”.

He recalls Finbarr’s Belfast trip for the making of Irish Traditional Accordionist, though points out that this was not technically his cousin’s first recording.

In the late 1950s, he says, broadcaster and music collector Ciarán Mac Mathúna “did a recording in our house in Ardgroom and John O’Dwyer came along, Murt Shea from Adrigole, Joe O’Neill, a fiddle player from the cross of Eyeries, my brother Riobard, and Finbarr was playing in it as well as a garsúnín - he was only maybe nine years old”.

Finbarr’s career as a composer began soon afterwards, one of his most famous tunes, ‘The Holly Bush’, written while a student boarding at St Brendan’s College in Killarney.

The tune, composed in the school billiards room while other students left for the weekend, recalled a holly bush back home in Cailroe. It was one of many inspired by Beara and by nature, Finbarr later attributing the singing of a chaffinch heard through a window as the inspiration for one of his best-loved continental-style compositions, the ‘Waltz of the Birds’.

The compositions kept coming during Finbarr’s initial 10-year sojourn in England, though his propensity for ornamenting and adapting the keys of existing tunes often made it impossible to distinguish old from new.

“Finbarr used to use me as a guinea pig in London when he’d be composing his tunes, testing them out to see if they were any good,” says Seán.

“He was a bit of a rogue as well. One time he played a set of three reels and the second one was one of his own compositions and it was a really beautiful piece of music. ‘Lord God,’ I says, ‘Finbarr, where did you get that second reel?’ ‘Oh, I got it somewhere,’ he says.

“He’d be very reticent and he’d never admit he’d composed a tune. He was very shy in many ways.”

Frank Conroy, who booked Finbarr and his various music groups while running the Jolly Butcher pub at Farnham Royal and the nearby Slough Irish Club, concurs.

“He was not a showman – he just played,” he says. “He didn’t say anything. He let the instruments do the talking but he had a huge following in London – they flocked to hear him play.

“He ran a couple of bands in England where he played pedal steel guitar, fiddle, and bluegrass, as well as traditional. He used to get a great response. He’d play the box, and of course the trad fellas in the audience would go mad, then he’d play bluegrass on the fiddle and they’d be jumpin’ and leppin’ around to that.”

Frank first asked Finbarr, a “fresh-faced young fella” to play for Slough Irish Society’s St Patrick’s Day celebrations in the late 60s as a treat for his own father, Galway accordion-player Paddy Conroy.

“We had all the great traditional players who were in London at that time… Brendan Mulkere, a great friend of mine, who died last year; Joe Burke, who died a few weeks ago and used to meet Finbarr there,” he says, adding that Dwyer and Burke “used to have great fun. They ended up partners of two sisters - Mary Conroy and her sister Anne [Conroy-Burke]”.

Frank, a keen photographer, recalls an incident illustrating the ribbing he says characterised the relationship between Dwyer and Burke.

“It was a Sunday morning and Burke was booked to play and Finbarr would always turn up to lend his support,” he says. “Burke turns up and he says, ‘I want you to take a photo of myself and Finbarr’. He stood behind Dwyer and opened up his jacket and he was wearing a t-shirt saying ‘World’s Greatest Accordion Player’. But Finbarr never knew.”

Next time the two accordion players arrived, the picture had been developed and the joke was revealed. “Burke produced the photograph in triumph,” says Frank.

“He was a mischievous fella but they got on very well, himself and Finbarr. They were two extraordinary talents, quite different, and it was a great privilege to have known them both.

“Finbarr had his idiosyncrasies and oddnesses but he was a gentleman and a generous man. He definitely was a genius, no question about that.”

After a 17-year void in which he played no music, Finbarr Dwyer returned to live performance, arguably “better than ever” in 2007.

Having built a successful business in London, he had moved back to Ireland, running The Lantern pub in Loughrea with partner Mary Conroy, when tragedy struck in 1989.

Mary’s brother Gerard was killed while navigating in the Donegal Rally in a car sponsored by Finbarr, who “took it badly”, precipitating his departure to England for a second time.

With the heyday of London’s Irish music scene waning, many musicians had made the move home, among them Finbarr’s friends Martin and Teresa McMahon, with whom he stayed for a period in Co Clare upon his eventual return.

“When he came back he had changed his style and I really did think he was playing better. He was playing the most fantastic music,” says Teresa. “Nobody will play like that again.”

Playing to audiences in Carraroe, Dolan’s in Limerick, the Merchant in Dublin, and venues the length and breadth of the country, the creative flame burned brightly, if unpredictably, until Finbarr’s health declined in the years preceding his death, aged 67, in 2014.

The composer of more than 30 tunes, his virtuosity as a performer remains legendary.

Mary Conroy, Dwyer’s long-time guitar accompanist, says: “Making music with Finbarr was fun.” It was “an adventure… with a loved and gifted musician who himself respected and loved music.”

“There was a surprise at every bar because he changed it around so much naturally,” adds multi instrumentalist and music historian Nicky McAuliffe. “If Finbarr made a mistake it’d be perfect – you’d think it was meant to happen. That was the beauty of listening to him because you’d never know what to expect.

“I heard him play the Holly Bush about five different ways – same tune with different pieces in, and all of them great. He was the king of improvisation.”