Kevin Barry: 'I take reality as a bit of a springboard'

Author Kevin Barry says the short story is a ‘very mysterious form and the more you do it, it’s like the less you know about them’. Picture: Darragh Kane

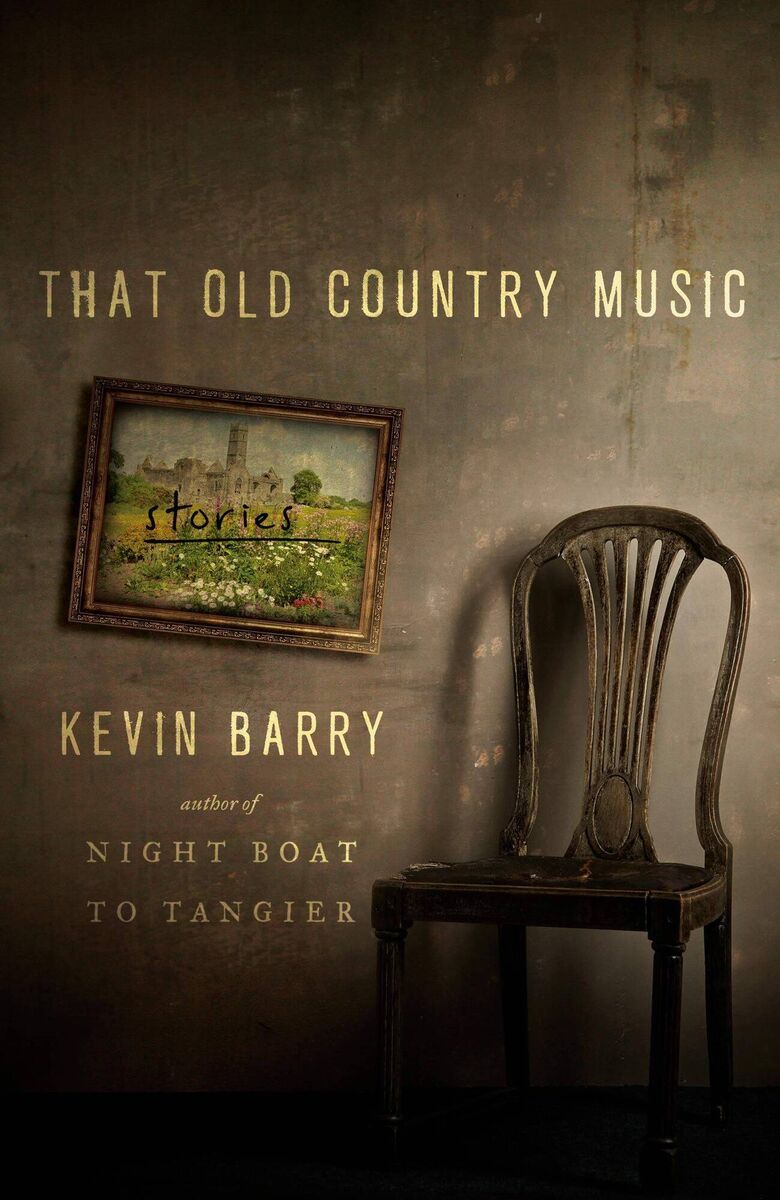

- That Old Country Music

- Kevin Barry

- Canongate, €16.99

WHEN Covid-19 first started to take off in Ireland and Europe at the beginning of March, Kevin Barry and his wife found themselves far from home in South America.

He describes the experience now with his usual mischievous wit: “It was a bit strange — it was down to the last couple of planes out of Uruguay, so everything turned into a thriller,” he laughs.

They arrived home safely to Sligo, and aside from feeling a bit shaken by the experience and following the news for a few weeks, life has now settled into its usual routine.

While thrillers aren’t normally his area of expertise, Barry is widely accepted as one of our foremost writers — particularly when it comes to short stories — and his third collection is a welcome sign that he’s not done with the short form yet.

That Old Country Music is a collection of 10 stories written following the publication of his last critically-acclaimed collection, Dark Lies the Island. They follow similar themes to his previous books: Rural isolation, the dark and mysterious psychology of places, and characters caught somewhere between poetry and catastrophe. Just because they’re well-worn topics for Barry doesn’t take away from the strength and impact of any of the stories, and the collection is simmering with his trademark impatient energy and flair for dark comedy.

‘Ox Mountain Death Song’, ‘Old Stock’, and ‘Extremadura (Until Night Falls)’ are excellent examples of his talent for portraying tormented and wandering characters with drama and affection. The dialogue is always absorbing, and there are plenty of sly one-liners that offer comic relief from the sense of melancholy that many of his characters are trying to escape. But his worlds aren’t all dark, and there are moments of lightness and love too in ‘The Coast of Leitrim’, ‘Roma Kid' and ‘That Old Country Music’.

Among the key elements that draw all of the stories together are their settings in isolated and rural areas, predominantly in the West of Ireland. It’s clear that Barry absorbs a lot from his surroundings, and most of the stories draw on the wild and dark landscape of the West coast and North West; while ‘Extremadura’ follows a homeless man in rural Spain. His interest in the psychogeography of places isn’t just theoretical; he’s happy to put the idea into practice too. When he talks fondly of his time spent living in the Beara Peninsula in the 90s, he mentions that he once composed a story in his head as he walked the 30km journey from Glengarriff to Castletownbere.

He’s very aware of the role locations play in the development of his stories, and explains: “When I write fiction, I always try to build myths around myself in terms of place. A place like the Ox Mountains if you drive through it, it will look like a small — and possibly dreary enough — wet range of little mountains in west Sligo. But something in my nature allows me to imagine these kinds of little films happening... to the point that I often write them on location.”

Another theme I suggest might bind the stories together, as well as being applicable to his earlier collections, is the mythology of normal people. The poet Theodore Roethke, the narrator of the final story ‘Roethke in the Bughouse’, is in the midst of a breakdown when he wonders whether he “can make [his] own mythology still”, and many of the stories follow the same vein of ill-fated figures trying to succeed in a world where misfortune and old magic are never far away. Are those topics he’s mindful of when he writes?

“I’m definitely inclined to mythologise, and the stories will very often tiptoe out towards the edge of realism. I take reality as a bit of a springboard I think, so that vaguely magical elements can sometimes come in.”

While Barry’s first two books were collections of short stories, in the interim he also published three novels, City of Bohane, Beatlebone and Night Boat to Tangier, as well as writing a play, Autumn Royal, and seeing his second collection Dark Lies the Island become a film.

Did the process of editing some of his previously-published stories into a new collection allow him to notice anything about his work that might have changed over the years?

“You definitely see yourself changing as a writer over seven or eight years; the tone changes a little bit as you get older,” he says.

“I found in my earlier collections, when I would write a kind of lyrical sentence, I would immediately try to take the piss out of it in the next sentence. I’d try to barb it almost, as a way of getting away with it. As you get older, you’re probably less afraid to pour it out onto the page and to just go with it.”

There’s a sense of confidence and control in all of the stories, as Barry has spent years honing his craft for striking dialogue and biting humour. Unlike some of his previous books, there is very little violence or conflict; but the stories in That Old Country Music are all the more impactful for their delicate undercurrents of destruction and heartbreak. ‘Ox Mountain Death Song’ follows the obsessive Sergeant Brown along the Sligo-Mayo border in pursuit of the doomed young Canavan, and the story treads the line perfectly between comedy and carnage.

‘Deer Season’ and ‘Saint Catherine in the Fields’ illustrate the devastating consequences characters can wreak with their decisions, but with a delicate and light touch. He shows different colours in ‘Roma Kid’, a tender, thoughtful story about an immigrant in Ireland. His sarcastic affection for isolated landscapes is clear in many stories. The narrator of ‘Toronto and the State of Grace’ explains that “the winter bleeds us out here” in a small town on the south -west coast, while the reluctant heartthrob in ‘Old Stock’ cites as a “cause of death: The West of Ireland”.

All of Barry’s novels have been critically acclaimed. Night Boat to Tangier was longlisted for the 2019 Booker Prize, Beatlebone won the 2015 Goldsmiths prize, and City of Bohane the 2013 Dublin International Literary Award — but stories were where it all started, and his passion for the format is obvious. He’s frequently asked to do university visits in the US; these days more often over Zoom, as his collections and novels are popular there. He recalls recently reading extracts of City of Bohane to a group of students, and while he admires the vitality in the book, he still finds going back to some of his older work difficult. “It’s an uncomfortable experience for most writers to read back over [their old work], but possibly less so with the stories. I still have one or two stories from earlier

collections that I’m very fond of and like to look at, and read for people still,” he says.

He recounts a time from his journalism days, when he interviewed the Scottish writer James Kelman for The Irish Times. He had just started trying to write short stories, and was mindful of asking Kelman questions that might offer some insight into how to best approach them. The advice sticks with him still, and despite two successful collections and an equally impressive third, he agrees that the short-story craft is something that becomes more challenging the more you write.

“It’s not easier that they get; they actually get more difficult as you go on,” he says. “It’s a very mysterious form and the more you do it, it’s like the less you know about them.”

It’s hard to believe, reading the sharp and absorbing stories in That Old Country Music, that Barry could find writing short stories a challenge, but after the publication of this striking new collection it’s a relief to know that he’ll persevere in mastering them.

“I still start loads of stories and try them, but most don’t work out. I’d say I manage one or two a year that I’m in any way happy with — but I think I’ll keep going.”