John Burke: The Cork teacher behind Wilton roundabout sculpture

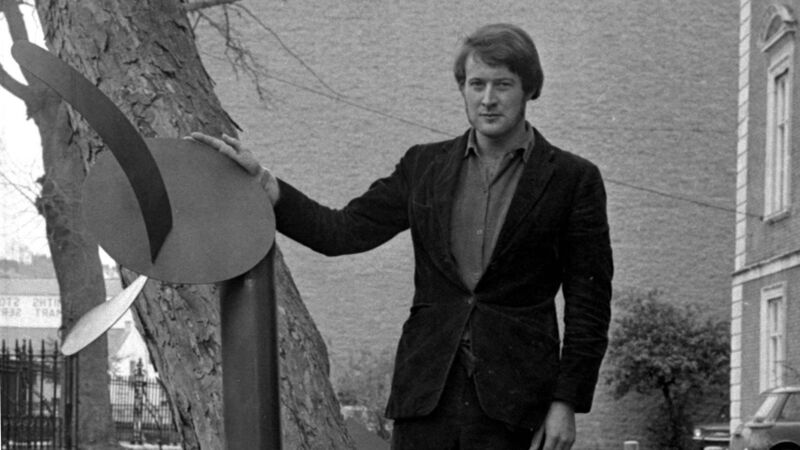

John Burke at the Crawford School of Art in Cork in 1973.

Pioneering sculptor John Burke is best known in his adopted city of Cork for his abstract steel sculpture at the Wilton roundabout. It's a piece of hard-edged public art that often perplexes people who, according to Catherine Marshall, "don't know how to perceive it".

Marshall, former head of collections and senior curator at IMMA (Irish Museum of Modern Art), is the curator of a retrospective exhibition of Burke's work in his native Clonmel. Taking place at South Tipperary Arts Centre (STAC) until September 19, the exhibition aims to shine a spotlight on the work of Burke who died, aged 60, from cancer, in 2006.

Marshall, as a board member of STAC, was surprised that when she suggested an exhibition of Burke's work, a lot of people weren't actually aware of him. "So I started arguing for an exhibition to bring John back to his home town," she says.

There is, she says, very little of Burke's work in Clonmel. "There's a piece on a roundabout on the edge of town but it's really not visible from the roadway. Once we started the campaign to have an exhibition of John's work, Limerick IT spent a lot of money restoring the roundabout sculpture. I'm very glad of that."

Burke, who was a member of Aosdana, is one of the most significant figures in the history of sculpture in Ireland in the second half of the twentieth century, says Marshall.

He introduced the use of steel and the welding process into a world of carved marble and cast bronze.

Influenced by his studies at the Royal College of Art in London and his travels in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and New York, Burke was also intimately connected with the city of Cork.

"In the 1970s, Cork was Ireland's leading industrial city with the dockyard at Verolme, Fords, Dunlops and Irish Steel. John connected all of that in a radical way. Sculpture everywhere in the world up to the 1960s was made from carved marble or cast bronze - quite precious material.

"John didn't invent (steel sculpture). He picked it up from big figures in the New York art world where he had an exhibition in the early 1970s. From studying in London, Burke came back to Ireland with this totally new aesthetic which is about making art out of things that were accessible to ordinary people; scrap metal found in dockyards, garages and farmyards. It was very different from the preciousness of fine art."

Burke, whose best known work is the Red Cardinal at the Department of Health's HQ on Lower Baggot Street in Dublin, taught a small bunch of students at the Crawford who went on to become major figures in the art world.

He had himself studied at the Crawford and nurtured the talents of internationally acclaimed artists: Maud Cotter, Vivienne Roche, Jim Buckley and Eilis O'Connell. Their legacy to Cork and Ireland is the National Sculpture Factory which they helped establish.

"Everybody loves the Red Cardinal which is a stunning piece," says Marshall. "If anything, Burke's pieces in Cork are even better and they deserve to be celebrated."

She cites a big yellow sculpture, Firefly, which Burke donated to CUH.

"He gave it as a gift to the maternity unit for a very particular reason which was typical of him in a nice human way. He wanted the sculpture to be the first thing the babies born there would see. As it happens, that piece has been placed in a different part of the hospital."

Burke's main influences were the American sculptors, Alexander Calder and David Smith, who worked with metal in a very playful way.

Bryan Kneale and Anthony Caro were also major influences on Burke.

When Marshall started to work on the exhibition, she was really only aware of his large scale work. "But through Frances Lynch, who was a close friend and supporter of John, I got to see his other work which we have in the show. It came from private collections, many of them in Cork."

Despite being collected by the cognoscenti, Burke's work, in particular his public sculptures, are generally misunderstood, says Dr Michael Waldron, assistant curator of collections and special projects at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork.

"As they are susceptible to weathering, it's understandable why these unusual forms might put people off. The artist's hard-edged abstraction might even make it hard to interpret.

"That being said, there is great ambition and invention in his work which results in bold and dynamic sculptural forms to be enjoyed aesthetically. In the right context, when cared for properly, these would be at home, even celebrated in any modern space."

Calls have been made for Cork City Council to refurbish Burke's untitled Wilton roundabout sculpture which has become dirty due to the high volume traffic that surrounds it. There is currently no budget identified for the maintenance of Cork's public art assets.

From about 2003 onwards until he died, Burke made a series of work which he called the Black Forest Series.

"I asked Frances Lynch if he had visited the Black Forest," says Marshall. "But she said this was a different black forest. It was psychological and was probably to do with his awareness of being on his own final journey."

Ever the individualist, Burke, who used to frequent the Hi-B bar, often in dark glasses, asked to be buried in a standing position on a height in Co Cork but within view of his native Co Tipperary. And so, he was buried vertically at Árd na Gaoithe cemetery, Watergrasshill, with a view of the Knockmealdowns and the Galtee mountains.