Culture that made me: Maureen Kennelly on her cultural influences

I’m the youngest of a family of seven. I grew up in Ballylongford, a very small village in north Kerry. The mobile library used to come to the village every fortnight. It was an epic event in my childhood. We lived on a farm. Going to a bookshop wasn’t a matter of course so the mobile library was an incredible treat. I can still remember that feeling of going up the steps and the excitement of seeing it open up in front of you, and getting as many books as you could. It was tiny. The width of it was maybe the span of your arms. It was so cosy. Floor to ceiling, it was full of books, nothing else. The driver would be in the front. You’d be in there on your own or with your mom or whoever else was dipping in that day. It was a complete sweet shop, an Aladdin’s cave territory for me.

Ballylongford is the home of the poet Brendan Kennelly, too – to whom I’m not related but I know him. Growing up, he was a regular presence on the Late Late Show so we were enormously proud of him. He gave us permission to be interested in literature and to write. It was a feeling of: sure look, if a fella from Ballylongford is writing, why not me? So I was writing poems from an early age and sending them off to David Marcus who was publishing New Irish Writing anthologies in the Irish Press. My older siblings, those who lived in Dublin, would say, “Oh, I bumped into Brendan on Grafton St. I told Brendan you’re writing poems and he said, ‘Keep up the good work.’” So there’d be nice messages filtering back down, and he used to send me very encouraging letters.

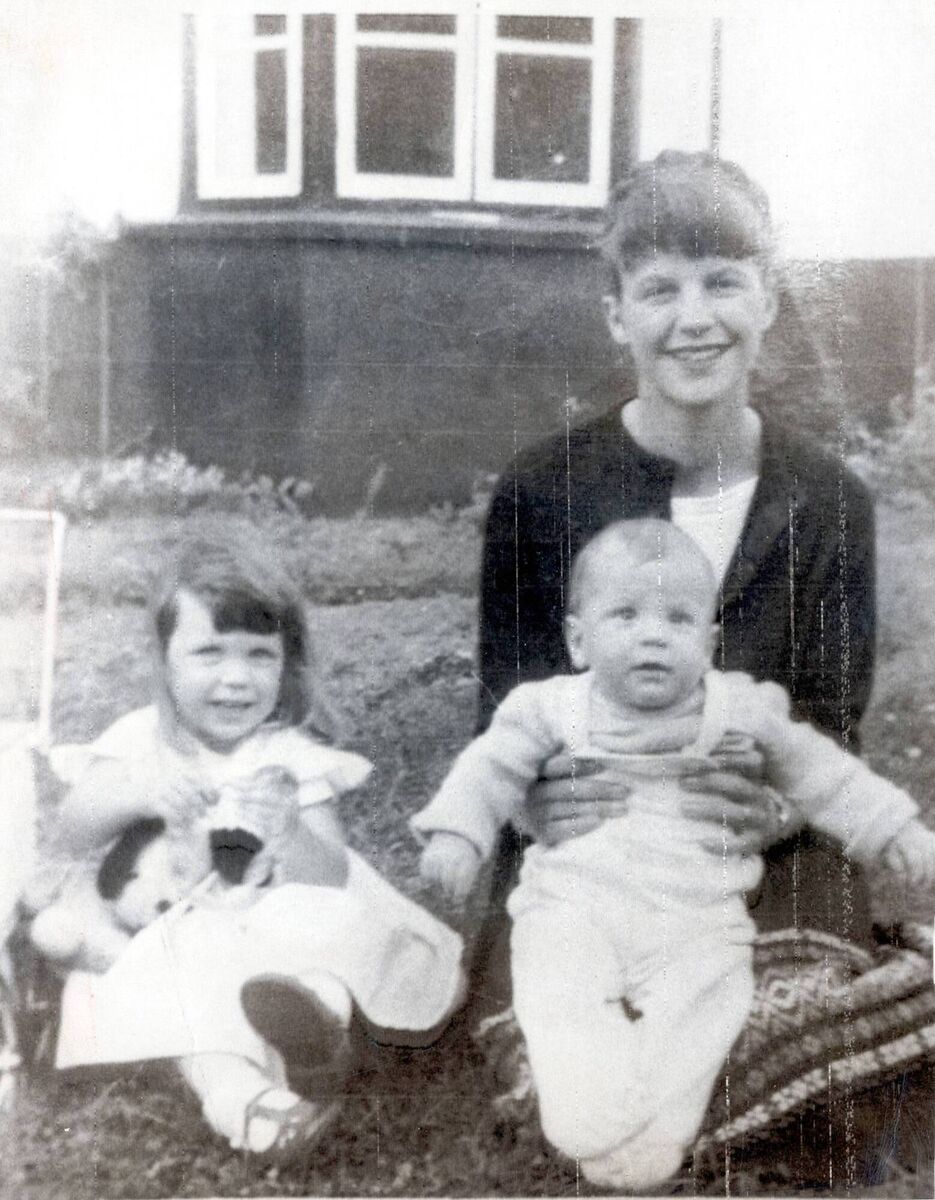

I remember my older brother Eoin bringing me home Sylvia Plath’s 'Ariel' and that being a really formative reading experience. Before that all of us of a certain age would have been listening to Pam Ayres’ jokey, doggerel poems on the telly so getting into this proper, grown-up poetry with Sylvia Plath’s beautiful Faber edition, a lovely pink book, would have been a big deal for me. It's a very personal collection of poems, very confessional. It was published after her suicide. The candour of those poems like Daddy and A Birthday Present said a lot to me, and her being a woman and challenging stereotypes resonated.

Illicit outings to the cinema in the afternoon When I lived in Dublin first – I went to UCD – I loved going to cinemas like The Stella in Rathmines. It always felt quite illicit going off to a movie in the afternoon. I used to love that! Being one of six people in the cinema. There was a great kick about it. Not that I was a deprived child, but to have that access a bus ride or a cycle away was an incredible thing.

When I was young, Druid were actively touring and I remember my mother bringing me to see Tom Murphy’s Conversations on a Homecoming. Séan McGinley and Marie Mullan were in it. I subsequently worked with Druid so you can imagine the excitement of me devouring all the old programmes and figuring out, OK, let’s see who exactly was in that show when I was 14 in Listowel. The play resonated with me hugely – the returned emigrant, the outsider who is present in all Tom Murphy’s work, the small-town snobbery. The feeling that the auctioneer is sneered at by Tom, the intellectual, as “you’re just a bunch of keys”. Those issues that bubble up in any small town are so sharply observed.

My mum is from Cork City. There were many jaunts to Cork. I remember going to see a pantomime in the Cork Opera House. It was a huge buzz – the setting was fabulous, the sense of showbiz, the goodies you were given during the pantomime. My mother’s parents’ home was on the Model Farm Road. I’ll never forget the excitement of sleeping in the bedroom and seeing the city lights outside the window. To me that was enormously thrilling – to think there was actually civilisation out there, with double decker buses flying around the place, as opposed to staring out to the gloom of rural Ireland where you can’t see a light for miles.

I broke both my hands in a bad accident when I was flung off a trailer full of turf. My father felt terribly guilty about it because he was driving the tractor. I spent a week in the general hospital in Tralee. To make up to me, he bought me my very first album, which was Paul Young’s No Parlez. It made it all worthwhile! My brother Eamonn had what was called a 3-in-1 HiFi system at the time. I presume it was radio, record player and cassette. He bought it at Castleisland on the proceeds of selling a bullock, which he had fattened. It was a big deal. He was – and remains – very entrepreneurial. I remember the excitement of coming home from hospital, all bashed up, and playing my Paul Young record. I was beside myself.

In the summer, a big focus for us was to go to the Atlantic Ballroom in Ballybunion on a Saturday night and maybe have a few pints. You’d somehow beg a lift or on occasion there was a bus service. I saw some great gigs like Mary Coughlan when I was 16. It was just brilliant. I remember loving her first album Tired & Emotional. She’s one of our finest talents, but she was just starting out then. The power of her performance was phenomenal. To see her in this sweaty nightclub in Ballybunion was fabulous.

In the mid 1990s, I volunteered for a year for Ken Monaghan, James Joyce’s nephew, at the James Joyce Centre. It's a really beautiful Georgian house in a rich area of Dublin. You’d walk up O’Connell Street towards Parnell Square, and this whole feel of the city changing, and becoming multicultural, is just so energising. I’m a big Walt Whitman fan. I think of his phrase, “I contain multitudes” – this city contains multitudes and is going to seriously prosper in the coming decades because now it has such a rich mix of people.