Cathal Dennehy: Raw and insightful, David Gillick's story of a race well run

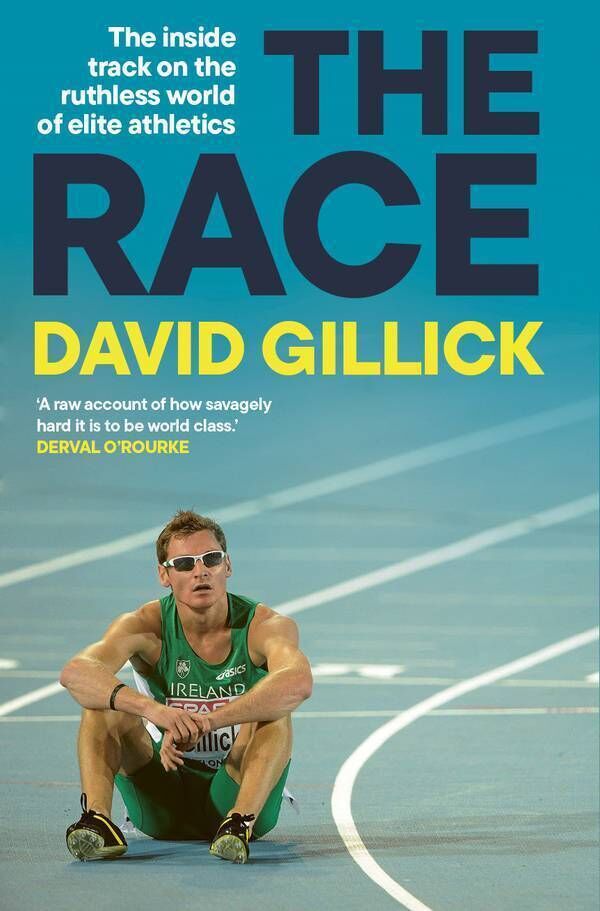

The 400m final at the 2010 European Athletics Championships is the race replayed most often in David Gillick's mind. Pic: Brendan Moran / SPORTSFILE

There’s a moment that sticks in the memory when it comes to David Gillick’s career – and it didn’t happen on a track. It was just after he made his last appearance in an Irish vest, running the 4x400m relay at the 2016 Europeans in Amsterdam, where the team fell just short of Olympic qualification.

A few of us hacks were gathered in the mixed zone and we began with one of those lazy starter questions: “What are your thoughts on that?” Nine years on, I can’t remember exactly what Gillick said but I know he talked for about three minutes, pre-empting every follow-up question we might have had and comprehensively capturing the race and his feelings. When he paused for further questions, none of us had any left to offer. He’d said it all.

The impression was clear from that succinct soliloquy: He’d go on to have a great media career.

Sure enough, a month later, Gillick was packing his bags for Rio, working at the first of three Olympics he has covered with RTÉ. His face is now well known to most across Ireland, but fame has a strong recency bias and, these days, more probably know him for his TV work than his athletics achievements.

Gillick is the first to offer a conciliatory hug or a joyous high-five when Irish athletes walk off the track. He’s been there, done that, and brings as much empathy to those interviews as personal insight. It’s why they strike such a chord. As Gillick’s mother once advised him, “You’ve got two ears and one mouth – use them in that order.”

By now, he’s someone that most Irish sports fans will feel they know – a clean-cut, well-spoken, sound chap, the kind you’d want your sister or daughter to marry. Of course, there’s far more to Gillick than that alone, and while working with him on his just-published autobiography, The Race, I came to understand that.

As his ghost writer, I’d be the most unreliable narrator imaginable to tell you whether the book is any good or not, but I can say this objectively: Those who read it will come away with a deeper understanding of elite athletics and what it took to become one of Ireland’s greatest sprinters. And it’s not often pretty.

The reality is that no one reaches the level Gillick did without being ruthlessly driven, that great motivation often breeding a single-minded selfishness. Some of the tales he told didn’t paint him in a flattering light and during the editing process, when he had the chance to reflect, I expected many to be chopped. But he left them all in. So another thing I can state objectively? It’s raw, it’s honest.

Whether it’s the pre-race insecurity that plagued him from childhood all the way to the Olympics, the explosive tantrums when it went wrong on the big stage or the dark, terrifying void he slipped into when his career ended, he tackled those subjects the same way he did his sport: by going all in.

Of all the championships that Gillick contested, perhaps the most influential was the 2002 World Juniors in Kingston, where he stood among throngs of Jamaican fans as a 15-year-old Usain Bolt powered to 200m glory. “For young, impressionable athletes, experiences like that have a seismic impact,” he writes. “At the time, I’d been juggling Gaelic football with athletics and had yet to choose which one I wanted to pursue. But as I’d stood in that stadium, looking around at that magnificent, intoxicating madness, it became crystal clear. Easier said than done, of course, with one of his Gaelic football coaches later confronting his sprints coach Jim Kidd, asking, “Why is he going off and doing this running stuff? He could play for Dublin one day.” It’s clear these days that Gillick retains a great love and admiration for Kidd and the coach who took him to the world final, Nick Dakin, though it’s clear he feels something different for Lance Brauman, who he trained with in Florida in 2010 and 2011 and who he hasn’t spoken to since.

The spectre of doping lingers in the background for much of his career, with Gillick becoming more cynical as it went on, especially after one of his chief rivals, LaShawn Merritt, tested positive for a steroid which the Olympic champion blamed on taking penis-enhancement pills. When he heard the news, Gillick flashed back to the warm handshake he received from a beaming Merritt before the world final. “Suddenly it felt different – hollow,” he writes. “You’re a fucking cheat and you’re prancing around, wishing everyone good luck”.

In Florida, he trained with three athletes who later tested positive, among them US star Tyson Gay, who he recounted was among the most outraged in the group after a documentary on Marion Jones aired on ESPN. “Did he only start doping later?” Gillick wonders. “Or was this all one huge act, one so convincing that it deserved an Academy award? I wasn’t sure, but either way I could only laugh at the hypocrisy.”

On the build-up to the 2012 London Olympics, the topic at training in Loughborough one night was which British athlete would “get a free ride to an Olympic gold medal,” he writes. “I didn’t understand what the others meant at first. ‘Well,’ said one of the lads. ‘Every time there’s an Olympic Games, there’s some home athlete who comes out of nowhere, wins gold, and they’ll be protected from testing positive.’ Loads of names were mentioned in the ensuing chat, but one name came up far, far more than the rest.” The dazzling highs of his career are dissected, relived, but what’s striking is just how fleeting those magic moments were – the prelude to one of the best beset by a panic attack, its afterglow plagued by a pressure to perform even better next time.

Trying to reach the very top in an individual sport inevitably causes friction in relationships and there’s no shortage of that with Gillick’s loved ones, his coaches, his teammates and national governing bodies. A city that will always have troubled memories for Gillick is Barcelona and the 2010 European 400m final: “Over a decade and a half on, it remains the one race that still replays in my mind, the one race I still run, searching, hoping, for a different outcome.” Having opted out of the 4x400m heats, his relay teammates made their feelings clear when he approached them in a bar that night: “I said hello and, as soon as I did, they stood up and walked out, not so much as acknowledging my existence as they left.”

There are parts of Gillick’s story where you’d wonder why anyone would choose this way of life, but of course those rare, intoxicating highs seem to make all the darkness worthwhile. After all, it’s possible to love something and hate it at the same time. With athletics, Gillick did both at different stages of his life but in the end, it’s clear the sport gave him so much more than it took away – and still does.

As he asks himself while sitting on the hill in Santry, reflecting on his career after running at Morton Stadium for the last time: “How f***ing lucky was I to get to do all of that?”