Kieran Shannon: Irish rugby's long journey still has distance to travel

DEAD MAN WALKING: Ireland head coach Eddie O'Sullivan in conversation with captain Ronan O'Gara before the Six Nations meeting with England in 2008. Picture: Brendan Moran / SPORTSFILE

When did some reporters suspect Joe Schmidt’s command of the Irish setup was on the wane?

A month out from the 2019 World Cup when the squad were on training camp in Portugal, the team management squared off an evening to have a few drinks with members of the media. After a couple of beers Schmidt rose to his feet, expecting his assistants to follow. Only they stayed put. “It was an awkward moment,” noted someone who was there. “It felt like there was a power shift, or at least that they were no longer hanging on his every word.”

As for when Eddie O’Sullivan discovered he had definitely lost his job?

The night before Ireland’s final game of the 2008 Six Nations, against England in Twickenham, his phone rang. It was Brendan Fanning, the rugby writer who had it on good authority the IRFU were “going to pull the plug” on O’Sullivan after the game. Cue another awkward moment, but one that O’Sullivan appreciated. Better that Fanning after 17 years of a working relationship gave him the heads up rather than O’Sullivan choking on his cornflakes the next morning upon discovering what it said in the paper.

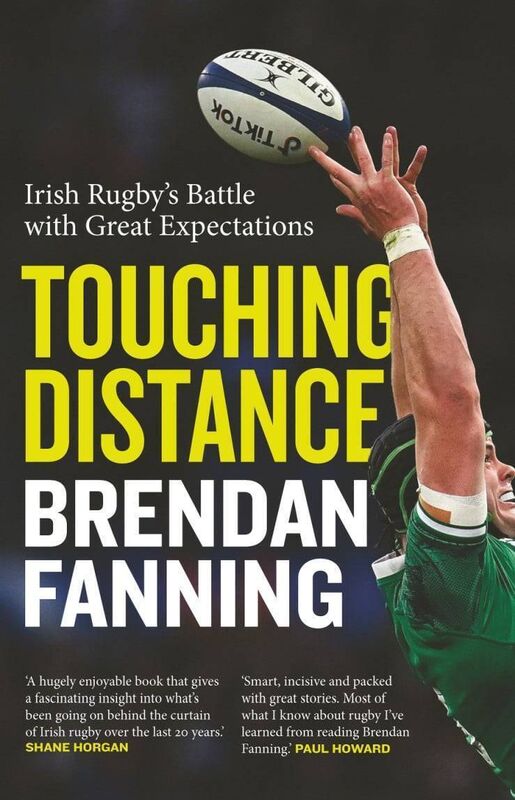

It’s hundreds of behind-the-scenes moments like those which make by the aforementioned Fanning one of the most engrossing and entertaining as well as informative Irish rugby books committed to print and possibly the best Irish sports book sequel ever.

Only a year before he made that call to O’Sullivan. Fanning produced , a brilliant account of Ireland’s journey from the dark ages of amateurism and then shamateurism to one of the more admired and professional setups in Irish sport and world rugby.

takes up where that left off. Back then Ireland were only winning Triple Crowns and only Munster were winning European Cups. Touching Distance explores how Ireland have gone on to rack up Grand Slams and Leinster Heineken Cups and even Connacht have won a Pro 12 – but all the while that coveted World Cup semi-final spot has remained elusive.

In the hands of a less skilled writer, this could have been a hard, earnest read; by examining the sport’s structures and pathways, it could have been weighed down by corporate and consultants’ speak. Instead it rips along because of Fanning’s capacity to marry laugh-out-loud yarns with cold-eyed observations.

The book’s first three chapters each revolve around a pivotal figure: O’Sullivan, Schmidt and Nucifora. All three co-operated with Fanning but what makes those chapters and the book so compelling and fair is that he counterbalances their versions of events with those of others.

We learn of how the Schmidt that Isa Nacewa and Tom McCartney knew in Auckland – “A really, really nice guy – if anything, too nice, a little too complimentary on guys” – was completely different to the one that showed up at Leinster – “a ruthless streak where he doesn’t take any prisoners”.

How O’Sullivan had the humility to call Philip Browne years after being let go and effectively blackballed by Irish rugby and ask what advice would he have for him, and be told his “communication skills” could have been maybe better. How O’Sullivan would have loved to mentor an Anthony Foley after his tenure with Ireland was over but how his old – and former – friend Liam Hennessy felt he could have done with a coaching mentor of his own, maybe his old college lecturer PJ Smyth, when he was with Ireland rather than be “the one, sole, authority”.

The middle section of the book delves into each of the provinces, again marrying stories with structures.

We learn that Rassie Erasmus reported to work at Munster a few days earlier than scheduled, even going to the bother of going into Limerick city with his wife and buying a Munster polo shirt “to feel a bit more comfortable” when walking through the door.

Ian Madigan mistakenly selected a loyalist bar on a team-bonding excursion only to learn when ordering his first pint that the regulars were fine with him being from Dublin. By his second one they were getting it for him. Stuart Lancaster gave a fine rendition of American Pie on a night out with the Leinster squad in Temple Bar. A day after securing and swearing Mack Hanson to secrecy that he was joining Connacht, Any Friend called his son back in Australia only to learn he already knew: Hanson happened to frequent the same bar as him and was “loose, but a good loose, maybe dance on the table and get his gear off but he’s not going to hurt anybody”.

All those provinces have stories but that can’t mask that they all have challenges and issues, something Nucifora’s successor as IRFU high performance manager, David Humphreys, is well aware of. While Leinster has 17 people working full-time in its schools, Ulster has just three, Munster two, Connacht none. As Fanning observes, “The city of Limerick is close to falling off the edge of the rugby schools map. In Ulster the number of competitive schools is paltry. In Connacht there is no tradition of high performance in the schools and the way forward may be via the clubs.”

The book also contains a good examination of the problems and solutions concerning the women’s game, thanks to Fanning picking the brains of Railway Union’s director of rugby, John Cronin. The problem, as he sees it, is that Irish rugby has had a subcommittee for women’s rugby controlled ultimately by men. “It has been run by people who just don’t get it. An aul lads’ convention.”

If men’s rugby didn’t exist the solution is – and still should be – to create performance-oriented operations where the players and universities are and create eight franchises – four in Dublin and one each in Belfast, Cork, Limerick and Galway.

Again though the book’s strength is in its anecdotes as much as its analysis. A subtheme is the relationships, many of them strained, between various key players. Schmidt and Kidney (“Joe knew far too much about rugby for Kidney’s liking,” says one insider). Nucifora and Stephen Aboud (“Steve was great,” says Nucifora, “but we should be encouraging people to come into the coaching game, not try and make it into some type of freaking doctorate”). Farrell and Lancaster, once England 2015 comrades.

The saddest and most detailed though is that between O’Sullivan and Liam Hennessy.

Hennessy admits he overstepped the mark in how he challenged O’Sullivan on the eve of the 2007 World Cup. And O’Sullivan admits to how that ended their relationship. “I know Liam since 1975 in Thomond College. I used to stay at his family’s home in Cappawhite. Liam’s still a great guy but he’s not a pressure guy.” They no longer speak.

“Yes,” O’Sullivan tells Fanning, “it is sad.”

But we learn of other bonds. Rassie Erasmus didn’t know Axel Foley would take to him when they were paired together in the summer of 2016. They immediately clicked over a few bowls of chowder on Clancy’s Strand. “Axel actually slapped me so hard on my back and hugged me,” Erasmus recounts.

Someday, he says, he wants to revisit Foley’s grave.

Maybe it’ll be next month when he and the Springboks return to these shores, though he’ll probably keep it private. Until, that is, Fanning maybe extracts it from him, in the sequel to Touching Distance, a decade or two from now. If Ireland by then have finally got their hands on the Webb Ellis, there’ll be no better storyteller of that journey from here to there.