Raising a toast to one of New York's most famous sons

American Democratic politician and governor of New York, Al Smith (1873 to 1944), his bid for the presidency was marred by anti-catholic and anti-immigrant feeling. Picture: MPI/Getty Images

Last Thursday night the Alfred E Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner, more commonly known as the Al Smith Dinner, was held in the Hilton Midtown Hotel in New York.

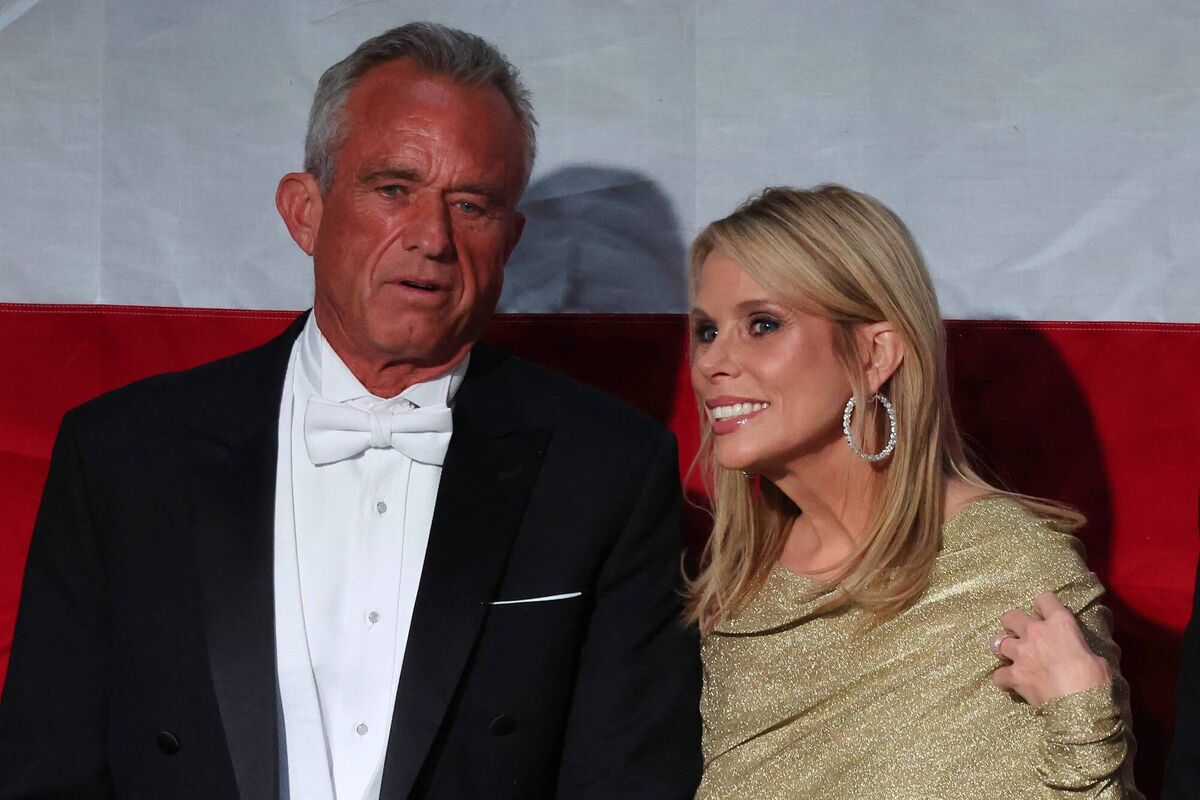

Donald Trump was there, though Democratic nominee Kamala Harris skipped the event.

The dinner commemorates the first Catholic to run for the presidency: Al Smith, someone whose life models the ascent and assimilation of Irish emigrants into the mainstream of American life.

Synonymous with corruption, Tammany was nevertheless the dominant political power in Manhattan, and when Smith was still a young man — personable, eloquent, tactful — Tammany saw his potential.

As governor of New York, Smith lived a long way from South St, occupying the governor’s executive mansion in Albany, but he was back in New York for his presidential run in the 1928 election.

By then Smith was a long way from South St. He was president of Empire State Inc, the corporation that built and operated the Empire State Building, and his move to an address not far from Central Park was a news item in the New York Times.

John F Kennedy, of course, became the first Catholic to become president and he paid a handsome tribute to Smith on the campaign trail in 1960.